He’s a poet of loneliness,” said California Book Club host John Freeman of Adrian Tomine, the author of the graphic novel Shortcomings, the month’s featured book. He noted that while he was growing up in Sacramento (where Tomine also spent his summers with his dad growing up), he felt that the city was “an urban landscape designed for dislocation and loneliness and feelings of that.” Freeman asked Tomine to talk about what made him want to draw stories about those feelings.

Tomine noted that his early stories aren’t explicitly set in Sacramento, but in his mind, they do take place there: “Even now, as an adult with a family, when I go back to Sacramento, I have the exact same feeling that I had when I was 16 there, which is…now, it’s kind of beautiful in a way because it’s finite, and I’m in control of how long I’m there.... I think that loneliness pervaded the work, but it was also the spark for the work.” He’s grateful for those periods of boredom where he spent time drawing.

Freeman asked how Tomine sees or draws character, pointing out protagonist Ben Tanaka’s hunched posture during a disagreement with his girlfriend, Miko, at the start of Shortcomings. “When you see a person, do you see their body language?” Freeman asked. Tomine responded that he does notice it, and he does think about how to communicate this to the reader, but he doesn’t draw body language in a strategic way, but by intuition. With Shortcomings, he said, he got particularly into posture, clothing, and gestures—it’s his most detailed, realistic book. While working, he would position a mirror next to his drawing board and make weird grimaces and try to replicate them with his brush.

Tomine explained that he thinks that some of the gesture work that Freeman pointed out can be terrible if thought about too explicitly while drawing. He finds it helpful to embody the character and to put himself into the imaginary situation. “Sometimes I’ll very bizarrely speak the conversations out loud in my studio,” he said. “It’s almost like a form of acting, or something like that, where once I’m inside that character, and I’m inside that scene, all the other execution becomes sort of spontaneous and unconscious.” After experiencing the scene, he transcribes what he’s just experienced.

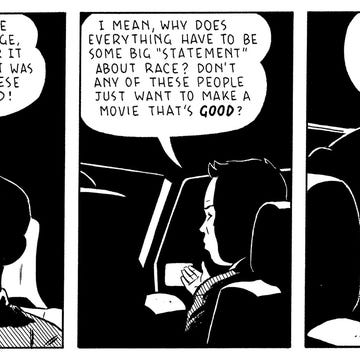

Freeman commented that addressing race and ethnicity head-on in Shortcomings was a choice Tomine hadn’t made in his earlier work. Tomine responded that making Ben Japanese American and his best friend, Alice, Korean American was a conscious decision, and that there was a vagueness to his work leading up to Shortcomings, not by design “but by ignorance or obliviousness.” Once his work became published on a wider scale, he was surprised to be described as an Asian American cartoonist and to be repeatedly asked about that—questions he hadn’t anticipated as a 15-year-old kid drawing in his sketchbook.

When Tomine started publishing with Drawn & Quarterly at age 19, he began feeling pressure related to the topic of race and ethnicity while doing interviews with Asian American publications. He made a conscious choice to address those questions and criticism he’d received, but a part of him still felt defiant, and he was adamant that he didn’t want to do the most “crowd-pleasing version of this story.” He wanted to make a book that “gave critics and journalists and readers what they wanted but also something that felt very honest.”

In hindsight, Tomine remarked, it was a mistake to make Ben look the way Tomine did then because it seemed to others like “a very thinly veiled autobiographical story,” which he thinks is not a correct reading of the work. Rather, he said, the way he worked was similar to what Charles Schulz had said about dividing his psychology across the cast of Peanuts.

Special guest David L. Ulin joined the conversation. He asked Tomine about the value of his early experience drawing comics for himself and not showing them—incubating them—and then putting together his own publication. Tomine responded that about 15 years ago, he developed an extreme feeling of self-consciousness around reviews of his books, particularly after reading online message boards, where people would anonymously tear up someone’s work. To combat that feeling, he began trying to trick himself into thinking that he’s still working in that same isolation.

If Shortcomings was him trying to listen and take into account people’s comments, his next book, Killing and Dying, was the opposite of that, Tomine explained. Ulin pointed out that in an earlier interview, they had talked about how Shortcomings was the apotheosis of a certain kind of style for Tomine, and that partly to break out of that, Tomine sought more-common store-bought tools that would help him push art in the way he wanted it to go. Tomine clarified that many cartoonists suffer and benefit from a degree of OCD or perfectionism and that that can lead to beautiful work, but that in his case, it felt unsustainable. Before working on Killing and Dying, he felt he was getting to the point where it wasn’t just about seeking perfection in the final image, but about buying the right tools, many of which were expensive and hard to find.

Tomine found it useful to look around, not only at comics but to other art forms, “at people who I had admired, and maybe their work wasn’t technically precise, but the net result of the work was very moving.”•

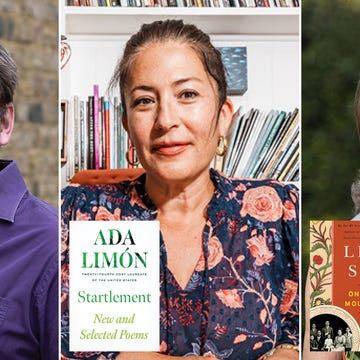

Join us on Thursday, September 18, at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when Amy Tan will sit down with CBC host John Freeman and special guest John Muir Laws to discuss The Backyard Bird Chronicles. Register for the Zoom conversation here.