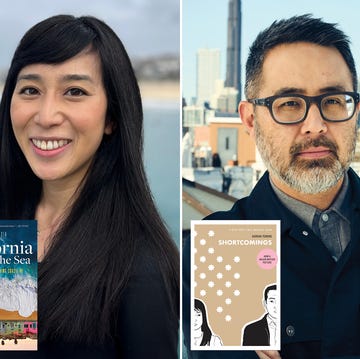

Ben Tanaka, the protagonist of Adrian Tomine’s barbed, funny, and daring 2007 graphic novel, Shortcomings, revels in his life of stasis. Comfortable in sparking spats with his girlfriend, Miko, and luxuriating in detached misanthropy with his best friend, Alice, Ben sees no reason to change. Indeed, early in Shortcomings, Ben notes to Alice, dismissively, “Anyway...I’m just saying that it’s Miko who’s changed, not me.” Only a 30-year-old would so blithely describe changing one’s perspective as “tiresome”—a clue that Tomine, with sardonic restraint, carefully seeds.

Shortcomings has aged marvelously in the two decades since its publication. A Japanese American wunderkind cartoonist, Tomine achieved acclaim with his Optic Nerve comics while he was still in his 20s. In the 1990s, the heyday of identity-politics discourse, some critics sniffed that Tomine avoided engaging with his Asian American identity. It’s tempting to read Shortcomings as a rejoinder. Happily, it’s much subtler than that.

Tomine executes many difficult maneuvers in Shortcomings’ 100 pages, gently prodding readers both sympathetic and skeptical. Ben, somewhat of a Gen X stereotype (he dropped out of grad school and manages a failing indie cinema), considers himself a put-upon truth-teller. When Miko tells him she’s moving to New York for a few months for an internship at a film institute, rather than congratulate her, Ben takes it as an opportunity to rant: “I hate the way everyone in the Bay Area worships New York! Trust me: it’s highly over-rated.” Ben tells Miko he’s not moving with her, proud of his fortitude. She immediately punctures his pomposity by replying, “I wasn’t really asking you to.”

Ben’s stability, bolstered by the narcotizing placidity of his East Bay life, reads as driftlessness—maybe even depression—to everyone who meets him. Indeed, Ben, who remains oblivious to himself throughout nearly the entire book, never acknowledges the common element of all his gripes: himself. That’s both aggravating and plausible. Who among us, in our lowest moments, can honestly view ourselves?

Those, like me, who find Ben sympathetic if stunted would likely treat him as a friend who seems stuck. He’s more of a jerk than necessary and his own biggest obstacle, as Alice tries to tell him (“I know it’s hard for you to see the bright side of things”). And those who consider Ben unpleasant, cocky, and even misogynistic have a lot of supporting evidence. Ben never admits that he might have pushed Miko away by belittling her artistic judgments and minimizing her claim that he incessantly gawks at blond white women. Ben thinks nothing of bringing up an embarrassing anecdote about Alice when she introduces him to her new girlfriend. It’s Ben’s world; we’re just living in it.

But even his detractors must acknowledge that sometimes Ben is right. Pace Tomine’s critics, Ben has some points about the limits of representation. Railing against a middlebrow film about Asian American families that closes with a scene featuring fortune cookies, he asks, “Why does everything have to be some big ‘statement’ about race? Don’t any of these people just want to make a movie that’s good?” Tomine slyly leaves unsaid the obvious rejoinder: Just because Ben doesn’t like something doesn’t mean it’s bad.

If Shortcomings responds to a demand that Tomine explore the dynamics of Asian American life, the naysayers may have buyer’s remorse. Tomine depicts private conversations among Asian Americans in the 2000s with blunt fidelity, from cringe-inducing allusions to penis anxieties to unflattering descriptions of the psychodynamics of interracial dating. I remember those debates—Were narratives of uplift necessary or merely tired? What do we owe the communities that raised us? Can we create art that centers us without centering whiteness?—with rueful fondness for our youthful passion. Even if the questions now feel a bit creaky, Tomine acknowledges that they felt important.

What makes Shortcomings still funny and fresh? For me, Tomine’s deft combination of narrative honesty and formal precision remains electric; Shortcomings would suffer in any other form. Because we lack a sense of the interiority of the characters, the deck never feels stacked for or against Ben or anyone else. Tomine doesn’t give clues as to when we should “approve” of anyone’s opinions. We can only take each character’s words at face value and decide what we think. But because the reader can see some emotional subtleties of the characters in each pane, Shortcomings avoids abstraction or didacticism. Ben, Miko, and Alice never become pawns or ciphers; Tomine draws each of them with specificity and agency.

Somewhat surprisingly, a few years ago, Tomine and the actor Randall Park adapted Shortcomings into a film, which Park directed and updated to the present day. The film retains the graphic novel’s fleet energy, wry humor, and East Bay charm. But I suspect no movie could faithfully preserve the spikiness of Tomine’s original.

After watching the film, I told the novelist Ed Park, who had recommended Tomine’s work to me before Shortcomings’ publication, that the film’s sunny ending was a bit disappointing. I felt it paled in comparison to the book’s bracing, brilliant final pages, in which Ben gets exactly what he wants and even deserves. Ed responded that the book’s conclusion “would have been too depressing.” I thought he might be right but argued, “We can handle it!” And as we debated the depiction of Asian Americans in popular culture and what seemed challenging versus what was satisfying, I felt a bit like a softer, grown-up Ben Tanaka—hopefully more mature but just as forthright.•

Join us on Thursday, August 21, at 5 p.m. Pacific time, when Tomine will sit down with CBC host John Freeman and special guest David L. Ulin to discuss Shortcomings. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

TRUE CRIME

Mark Athitakis reviews Peter Orner’s The Gossip Columnist’s Daughter, which will also be the subject of a forthcoming Alta Live. —Alta

MISSISSIPPI MURDER INVESTIGATION

Development of a television series adapting past CBC author Percival Everett’s novel The Trees, centering on two Black detectives investigating the murder of white men, is underway. —Kirkus

“YEAR OF THE PYNCH”

Devin Thomas O’Shea writes about why Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland is the novel we need right now. —Literary Hub

THE PICTURES GOT SMALL

Athitakis reviews David M. Lubin’s Ready for My Close-Up: The Making of Sunset Boulevard and the Dark Side of Hollywood. —Los Angeles Times

Alta’s California Book Club email newsletter is published weekly. Sign up for free today.