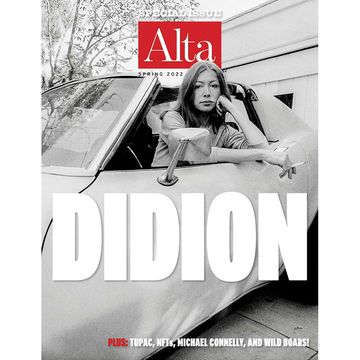

I like to think about a book as an iceberg,” Julie Golia was saying. “The published thing is just that little tip that sticks out.” This was on a Zoom call early in March to discuss the Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne Archive at the New York Public Library’s Fifth Avenue building, where Golia is associate director of the Rayner Special Collections Wing and the Charles J. Liebman Senior Curator of Manuscripts. The archive, which opens to the public on March 26, is itself a kind of iceberg: 336 boxes of notes, manuscripts, correspondence, and personal items, spanning, in Golia’s words, “literally birth to death.” Or even more than that, since among these holdings are both genealogical materials tracing Didion’s family history and a program from the author’s 2022 memorial service at Manhattan’s Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine.

Thanks to Golia and Meredith Mann, assistant curator of manuscripts, I had the opportunity last week to take an early look at the archive—or a small piece of it, at any rate. We met in a research room at the library, where the two of them spent an hour or so walking me through a selection of artifacts. There were the canvas director’s-chair backs from the set of the couple’s final film collaboration: “John Dunne Up Close and Personal” and “Joan Didion Up Close and Personal,” these items read. There was Didion’s 1964 daybook, with a note scrawled in pencil in the space for January 30: “Oh NO!” it declared. A case of nerves, Mann suggested, since this was the day that Didion and Dunne were married. The assessment was supported by the following day’s more settled entry: “I’m smiling again.”

Also included were some materials I had specifically requested, among them the 2006 citation from the Los Angeles Times presenting Didion with the Robert Kirsch Award, for lifetime achievement. The evening she had received it, I’d spoken with her in the greenroom of UCLA’s Royce Hall, where the ceremony took place, and later I watched her accept the prize. To see the citation again, displayed on a long library table covered with folders and documents, was to recognize another form of reach, another blurring; let’s call it the presence of the writer in the world.

Such a presence, I’ve come to believe, is essential to understanding Didion and her writing, as is the relationship, personal and professional, she shared with Dunne. It’s a kind of blurring that requires us to regard her anew, to recognize that all of the strands via which we consider her career—essayist, screenwriter, collaborator, Californian—are facets of a more extensive whole. Think iceberg again, the published work merely the tip of a multilayered floe of ideas and influences, too capacious to be encapsulated through a single lens. That this is true for all of us should go without saying, which is one reason I am drawn to archives, because of how they serve to humanize even the most paradigmatic of careers, gathering, as they do, the pieces of the puzzle, the private writings, the datebooks and the diaries, the notes and early or unfinished drafts, the books and ideas that never quite panned out.

This depth, this scope, Golia told me, was a key element in the library’s decision to purchase the archive, which she first examined in late 2022. “I went in,” she acknowledged, “with the great question I think everybody has about Didion, which is: California or New York?” Nonetheless, from that initial encounter, Golia said, she felt “very strongly that the materials belonged not only in New York but at the New York Public Library, not because there isn’t remarkable representation of California in them but because in a lot of ways Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne were already at the library in over a dozen collections: in the papers of the New York Review of Books or Farrar, Straus and Giroux, in the papers of contemporary writers like Tom Wolfe.”

What Golia was referring to was literary infrastructure, which represents a narrative, or heritage, of its own. We like to envision writers as solo operators, but while this is accurate to an extent, literary work is also by its nature collaborative, relying on a network of agents, editors, readers, friends. The evidence for this is all over the materials I examined. In a 1964 letter, for instance, Betty Friedan apologizes that a story solicited from Didion for a magazine Friedan was guest editing had been turned down by the other editors. “If it’s any consolation,” she writes to Didion, “the company of fiction writers who wrote, in vain, at my request is somewhat more distinguished (Nobel and Pulitzer Prize winners) than those who are finally going to see print.”

That this note was sent to an author who, at the time, had published just a single book, the 1963 novel Run River, offers its own telling bit of context about Didion and how she had positioned herself.

Then there’s perhaps my favorite of all the items I surveyed, a 1965 letter from Billy Wilder, thanking Didion for a positive review in Vogue of his film Kiss Me, Stupid, which had otherwise been reviled by critics for vulgarity. “Dear Joan Didion,” it reads in its entirety, “I read your piece in the beauty parlor while sitting under the hair-dryer, and it sure did the old pornographer’s heart good.”

Ephemera? Of course it is. But that’s another function of an archive, to allow us to see the story underneath the story—and, in so doing, to expand, or reconsider, our point of view. This is essential in terms of Didion and Dunne for a variety of reasons, not least that—despite their fame or even notoriety—the two remain misunderstood.

As an example, let’s return to the issue of California and New York, which, when it comes to Didion and Dunne, is more nuanced than it might at first appear. Yes, Didion was, to borrow the title of her 1982 essay about Patty Hearst, a “girl of the golden west”—born and raised in Sacramento, educated at UC Berkeley. And yet, there is a parallel lifeline that unfolds in Manhattan, beginning in 1955, when she was selected to participate in Mademoiselle’s summer guest-editor program (the archive contains a specially bound hardcover edition of the issue on which she worked), and continuing through the years she worked at Vogue, before she and Dunne married and fled the city for Southern California in 1964. “There were years when I called Los Angeles ‘the Coast,’” she writes at the end of “Goodbye to All That,” the 1967 essay about her repatriation, “but they seem a long time ago.”

Two decades later, the couple would return to New York, taking up residence in the Madison Avenue co-op where he would die and she would spend her final 33 years.

Their departure would lead Los Angeles writer Carolyn See (whose 1999 novel, The Handyman, appears in the archive with a letter from producer Andrew Lazar gauging the couple’s interest in developing it for the screen) to label them “cut flowers,” but there’s more to it than that. In part, this has to do with the overlap Golia mentioned, their correspondence that is found in other holdings, the net cast wide again. Equally important is the role they played, even when living in Los Angeles, as California whisperers for New York publishers and magazines.

For Didion, of course, such a perspective has long been a filter; it animates pieces from “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream”—“October is the bad month for the wind,” she writes there, invoking the Santa Anas, “the month when breathing is difficult and the hills blaze up spontaneously. There has been no rain since April. Every voice seems a scream”—to “Los Angeles Notebook,” “Pacific Distances,” and “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.” I can’t help thinking, however, of Dunne as well, not only his novels but also Delano, the 1967 account of the California grape strike that Didion helped him report, and the 1978 essay “Eureka!,” in which he offers this trenchant bit of analysis: “Los Angeles is the least accessible and therefore the worst reported of American cities.… Distance obliterates unity and community. This inaccessibility means that the contemporary de Tocqueville on a layover between planes can define Los Angeles only in terms of his own culture shock.”

It makes sense, then, that New York would, and should, be part of the fabric of their careers, a key strand in their literary DNA. Not only for their own visibility but also because it allowed them to help carve out a place for California in a national literary culture that has long been hostile, regarding the state and its writing as parochial or regional rather than a defining American and global sensibility.

That quality of intention extends to the archive, which Didion and Dunne seem to have imagined as an opus in its own right. “It is not a hodgepodge,” Mann explained as we circled the table to look at work notebooks and draft materials. “Maybe I’m just being reverse influenced into thinking that she was very organized, but I think of a system.” Interestingly, this emerges in the materials pertaining to both finished works—the couple’s novels and nonfiction—and those left incomplete.

Consider a folder marked “Et Cetera,” which contains a few loose pages of typescript as well as some notes handwritten on graph paper. “How can we write the truth about ourselves?” Didion wonders there. “Do we even know it?” The rhythm of those sentences recalls the opening of The Year of Magical Thinking, but the questions feel epicentral to the entirety of Didion’s project: her fascination with façades and image, her distrust of resolution and of narrative. In the archive, everything is preserved, not because it answers all (or even any) of the questions but because the necessary inquiries, the concerns of living, linger even after death. I think of Dunne’s posthumous novel Nothing Lost, for which, the collection’s finding aid asserts, “Didion preserved Dunne’s notes, notebook, plot outline, chapter and manuscript drafts (many containing Didion’s edits), and research binders.”

Here we see the other revelation of the archive, which has (how could it be otherwise?) been hiding in plain sight all along. This is the matter of the authors’ collaboration, not only on their five produced screenplays and two teleplays but on the more granular level of their daily writing lives. Nothing Lost represents a case in point, Didion stepping in to oversee its publication, one writer taking up the mantle for the other, as they did repeatedly throughout their lives. The drafts and manuscripts of each bear notes in the other’s handwriting, which is why an archive such as this would be unimaginable—incomplete—without the presence of them both. “I think it really represents the breadth of their careers,” Golia said of the collection, “the breadth of their lives and their relationship and their ongoing, decades-long working partnership. It really exemplifies that for these two writers, those things can’t be teased apart or taken apart.”

Archive as mirror or reflection, in other words, even when what it casts back at us is broken or unfinished. Life as the stuff of process, process as the stuff of art. And now, the raw elements of Didion and Dunne’s processes will be available for anyone to peruse and study, regardless of affiliation or academic pedigree.

Talk about another iceberg. Talk about a means to reimagine two writers, and the relationship between them, in a variety of ways. “We have a lot of people coming in on the first day to look at these materials,” Golia told me during that initial Zoom call. “That’s really exciting. The library is very proud of the fact that we welcome all kinds of researchers to our special collections. I think, traditionally, there’s an assumption that you have to be a scholar, you must have a project to have access to these materials. But over the past several decades, we have cultivated students, journalists, teachers, artists looking for inspiration. People shouldn’t have to justify why they want to access the materials.”•