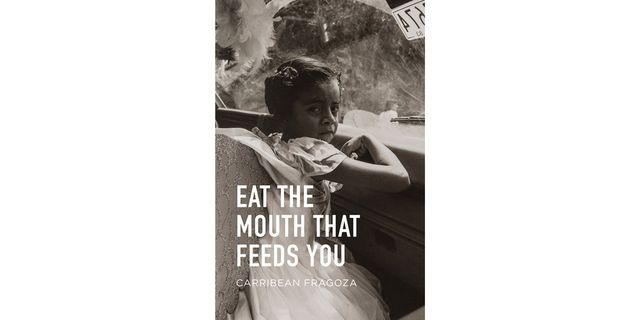

Sometimes the most enduring art is as much an act of love as it is one of resistance against injustice,” Carribean Fragoza writes in her essay “Toward a Radical Arts Practice.” It’s a sentiment that pervades the 10 stories in her collection of short fiction, Eat the Mouth That Feeds You, published in 2021. For Fragoza, art involves engagement, but it is also personal. Or perhaps it’s most accurate to say that these dualities do not apply.

Blending the physical and the metaphysical, the work in Eat the Mouth exists outside the bounds of category. Better yet, it occupies a category of its own.

This article appears in Issue 25 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

In part, this has to do with Fragoza’s commitment. Raised in the San Gabriel Valley, she is the founder of the South El Monte Arts Posse (SEMAP), a community art initiative created to reframe old (and often racist) mythologies of place. Eat the Mouth unfolds in a related but more elusive region, which James Baldwin once referred to as “a region in my mind.” It’s no stretch to suggest that Fragoza’s work emerges from, and expresses, a similarly incisive point of view.

My favorite story in the collection may be “Crystal Palace,” in which a Guadalajara salesclerk returns to the boutique where she works to discover the store’s demure owner having a tantrum over the end of an affair. (Full disclosure: I published the piece in Air/Light, the journal I edit at the University of Southern California.) Still, even to use the word “favorite” in relation to these writings feels like missing the point. All 10 narratives are so vivid, so distinctive; all 10 create universes of their own.

Take the title effort, which begins, “My daughter, for lack of memory, eats me. Sometimes in little bites throughout the day.” Such a statement is metaphorical, but within the story, it is also true. In Fragoza’s universe, what happens is more than allegory. She means to turn allegory on its head. What do children do, after all, if not eat their mothers? This is both literal, in the sense of feeding, and figurative, in terms of the energy they require. “Now look at me, mija,” the narrator warns. “Take whatever you can now. There’s not much. I don’t know how much more I have to give.”

Fragoza is addressing the limitations of the body, which are also the limitations of the heart. She is writing, too, about memory, which infuses every story here as if it were a physical force. In “Lumberjack Mom,” another mother subsumes her grief about her husband leaving by chopping down the lime tree they once planted in the yard. In “Me Muero,” a young woman narrates the aftermath of her own death. Alive but at the same time no longer living, with a body “now so brittle that I can no longer use it without parts of it falling off,” she gives an account that is gothic yet not without its own strange brand of hope.

“We are waiting for everything to break up into dust and carry away into the wind,” the character tells us in the closing sentences of the collection. “This is turning out better than I expected.”•