I am a 100 percent believer in strong gun control,” Berkeley-based photographer Judy Dater told me in September shortly before the opening of The Gun Next Door, her latest exhibition at Oakland Photo Workshop. “I don’t have a gun. I’ve never shot a gun. I believe we would all be safer if no one had a gun. But I also see we have a huge problem with so many guns out there, and we really need to understand why so many people in this country feel they need to have one or two or several hundred.”

We were talking just over a month before the mass shooting and manhunt in Lewiston, Maine, made national headlines. One of the ongoing tragedies of contemporary life is that anytime you speak or write about gun violence, you may find yourself confronted with a new, fresh horror.

A pioneering feminist artist renowned since the 1970s for her psychologically expressive portraiture, Dater has been wrestling for years with the nation’s response to the post-Columbine explosion of gun violence. Thinking about guns, she found herself wondering, as she put it, “What kinds of people have guns? And why?”

Dater, now 82, thought she’d be able to answer those seemingly simple questions by doing what she has always done best: using her camera to understand people better. She started by inviting gun owners to her studio to sit for portraits while holding their firearms.

On view for the first time and running through November 19, The Gun Next Door is an unsettling series of ambitious, provocative images. They may be Dater’s most transfixing and troubling works to date.

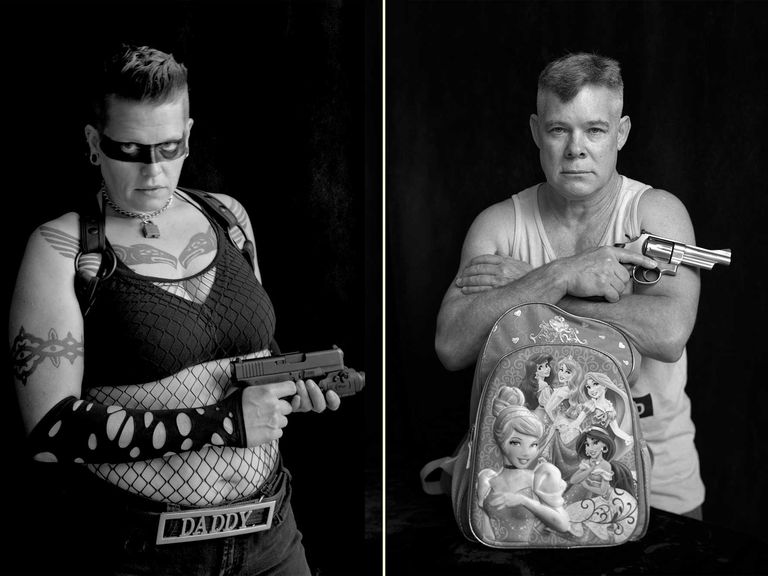

Eighteen large-format black-and-white images, representing about half of what Dater has shot—some portraits printed as large as 30 by 40 inches—show men and women, young and old, most gazing directly into the camera and holding their personal firearms. Dater’s subjects look calm and unapologetic; none fit neatly into any stereotypes the viewer may hold of gun enthusiasts. Among those photographed were a poet, a tech manager, a doctor, a surgical assistant, a civil rights activist, a merchant sailor, two veterans, a self-described pacifist, and more than one vegetarian.

Millions of Californians live with guns in their homes: 5.2 million, to be exact, or 17.6 percent of all adults in the state, according to a 2021 survey conducted by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. CBS reported that an estimated 28.3 percent of adults in California had guns in their homes in 2021. And yet, despite widely reported gun ownership statistics, which are republicized in the wake of every horrifying mass shooting (for instance, that the United States has an estimated 120 guns for every 100 people and that almost 20 million new guns were purchased in 2021 alone), the reasons people want to own guns, like everything about the gun debate, are complex.

For some, guns are a sanctified cornerstone of a time-honored way of life; to others, every firearm is an abhorrence. Our culture romanticizes and demonizes guns in equal measure.

The issue grows thornier within California, where residents in the overwhelmingly Democratic and left-leaning metro areas like Dater’s are prone to assuming, wrongly, that gun enthusiasts are sequestered in the state’s redder, more rural regions. The truth is that wherever you reside, as the title of Dater’s series makes plain, there could be a gun next door.

Seen collectively, Dater’s gun owner portraits confound expectations and have the power to trouble viewers—including this one—more than any stats or graphs about gun ownership could. The images captivated my attention but also made me deeply uncomfortable. Perhaps that’s because Dater’s photos suggest that the question of who among us has guns has only one resounding answer: everyone.

Dater traces her interest in addressing the gun debate through her photography back, fittingly, to art itself. She recalled visiting David Zwirner’s blue-chip Chelsea art gallery during a trip to New York in 2013, a year after the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre, and seeing a black-and-white painting of a gun hanging on the wall of an upstairs office.

“It was painted in a way that made it look animated, as if it had just been shot,” Dater recalled. She didn’t know the artist but snapped a photo of the painting and taped it to her computer back home. “I found myself looking at the symbology embedded in this object that just held so much information and power, and it made me think, I want to deal with this issue.”

After some failed experiments with gun imagery, Dater thought, What am I doing? I’m a portrait photographer. I should just try to take pictures of people with guns and see what that shows.

Friends suggested she “go to Texas, or someplace like that, where everybody has a gun,” she said. Instead, Dater got up the courage to broach the taboo subject with friends and neighbors, asking if they owned guns or knew gun owners.

Word of mouth led her to all of her subjects. She recalled a dinner party where she met a retired British epidemiologist who used to teach at Stanford: “He said, ‘Oh, I have a gun.’” Then he told Dater about other gun owners. “They were people I already knew, and they were all intellectuals. It wasn’t like they fit any stereotypical ideas of who has a gun and why. I quickly knew I didn’t need to go anywhere else.”

A photo of that bearded, 74-year-old professor emeritus, Andrew M., now hangs in the Oakland exhibition. In it, he’s gazing down at Dater’s lens, seated and comfortably balancing his rifle between his legs against the chair. He’s not exactly menacing, but he’s hardly inviting. The label on the wall includes his own words from a conversation with Dater: “I live in the world’s biggest liberal bubble in the Bay Area and most of the people I know are afraid of guns. I keep wanting to tell them everybody in America is armed to the teeth except YOU!”

Dater’s studio process, even with this potent subject matter, was much as it has been for the majority of her working life. She asked sitters to wear their own clothes, and there was minimal staging. They spent about an hour in conversation as she snapped their portraits with her old-fashioned large-format camera on a tripod, her head under her focusing cloth.

“I didn’t tell them what my agenda was. I didn’t even know what my agenda was,” she said.

She did insist they leave their ammunition behind and make sure their guns weren’t loaded. “They brought them in locked cases and showed me they were empty.”

Was she anxious, as an outsider to gun culture, having the firearms in her studio?

“Not at all,” Dater said. “Only [with] the one person who came with 10 guns and told me they had 200. That made me a little nervous.”

In one of the exhibition’s most captivating images, Thomas B., who has sad eyes and is wearing a tank top, holds his pistol with folded arms on top of a Disney-princess backpack. He’s a civil rights activist with the San Francisco chapter of the Pink Pistols, an LGBTQ gun rights group.

During my visit to the gallery, in Oakland’s Chinatown, Vincent Donovan, co–executive director of East Bay Photo Collective (EBPCO), which operates Oakland Photo Workshop, walked up to one of the framed photos and covered up the gun with his hand. “This person is telling us a lot, and if you remove the gun, it’s still an intense photograph,” he said. “These are portraits of people, not of guns.”

As I strolled through the gallery, taking my time before each image, I found myself agreeing. I was drawn in to these faces, to their eye contact with Dater, and by extension with me. They looked like people I might see at the supermarket or at a sporting event. It was only after several beats that I found myself registering their guns. That’s when I wasn’t sure what I felt.

Dater has shown her work all over the world, including in a major retrospective, Only Human, at San Francisco’s de Young Museum in 2018. But when she showed curators from various institutions her images from The Gun Next Door, no museum would touch them, she said. “They all liked the work, and one said, ‘I wish we could show it.’”

“I think they were afraid of it because of the subject matter,” she said.

For Donovan and the EBPCO executive team, Dater’s provocative series “felt right in line with our mission,” he said. “All our exhibitions are about the human experience. Gun ownership is an aspect of the human experience, and Judy’s images are completely honest about that.”

“It took some of us a couple weeks to get on board, because we have complex relationships with guns,” explained gallery manager Jyoti Liggin. But ultimately, context mattered. The gallery, after all, is in the heart of Oakland, a city fighting its own long battle against gun violence.

Dater’s work speaks a potent visual language, but it always originates in conversation. She poses more questions than answers. Earlier in her career, that meant asking, for example, What does it mean to be a woman in a male-dominated field? What’s the relationship of a woman’s nude body to the landscape? And how does power shift when a woman photographs nude male subjects?

Dater, who grew up in Los Angeles, moved to San Francisco in 1962 to study photography at San Francisco State University. As luck would have it, she fell in with Imogen Cunningham, Ansel Adams, and Brett Weston, founding members of the legendary West Coast Group f/64, which launched in the Bay Area in the 1930s.

Whereas the men in the group favored landscapes—rippling sand dunes and mountainscapes that evoked the vastness of the natural world—Dater was drawn to portraiture. She made a series of striking conceptual self-portraits in the desert Southwest. “Seeing a person in relation to the environment was always more visually interesting to me,” she said.

Cunningham, the revered doyenne of San Francisco photography, became a mentor and appears in Dater’s best-known photograph, Imogen and Twinka at Yosemite (1974). A re-creation of Thomas Hart Benton’s painting Persephone, it shows tiny, 90-year-old Cunningham (black coat, white hair, heavy Rolleiflex around her neck) looking startled by the sight of a naked, beautiful young woman (model Twinka, Wayne Thiebaud’s daughter) on the other side of a redwood tree. Recognized all over the world, the photo was the first full-frontal nude to run in Life magazine, in its 1976 issue celebrating women.

Like any artist with one massive hit in their oeuvre, Dater prefers not to dwell on the almost-50-year-old image. She has called it “a blessing, and also a curse,” because so many people know the image but don’t know it’s hers.

She said that a career spent taking portraits and self-portraits prepared her to tackle her “most overtly political” subject matter in The Gun Next Door.

Her political intentions softened, however, as she got to know her subjects, reminding me of Michelle Obama’s oft-quoted line “It’s hard to hate up close.”

“I thought I was going to make an antigun statement, something that would show clearly, Look how bad guns are. We have to take some kind of action. We have to do something,” Dater told me. She assumed, given her passionate antigun stance, that her subjects were “all going to look like bad people because they’re holding a gun.” She thought of Arnold Newman’s famously devilish 1963 portrait of Nazi arms manufacturer–war criminal Alfried Krupp and imagined that her judgment of gun owners’ choices would come through in her depictions of them.

“But in the end, I couldn’t do it. I talk to people to get them to trust me, to open up to me and feel comfortable. And in doing that, they just became another human being. It’s the way I’ve always worked. I want to show the best in people and the mystery and complexity of people. I wouldn’t say it was irrelevant that they were holding the gun. It just made it more strange, that this is a normal person.”•