Alta Journal is pleased to present the fourth installment of a five-part original series by geologist and author Ruby McConnell tracing the creation of the Applegate Trail.

After losing two of their children to the hazards of the original Oregon Trail in 1843, Jesse and Lindsay Applegate and their party charted an alternate emigrant trail connecting the southern Oregon Country with Fort Hall, Idaho, in 1846. Before their trail was made safely passable, the first group of emigrants set out on a journey that would prove fatal. Ruby McConnell brings the story of the Applegates and other tales of the American West to life through her extensive research of archival material and reporting in her forthcoming book, Wilderness and the American Spirit (Overcup Press, 2024).

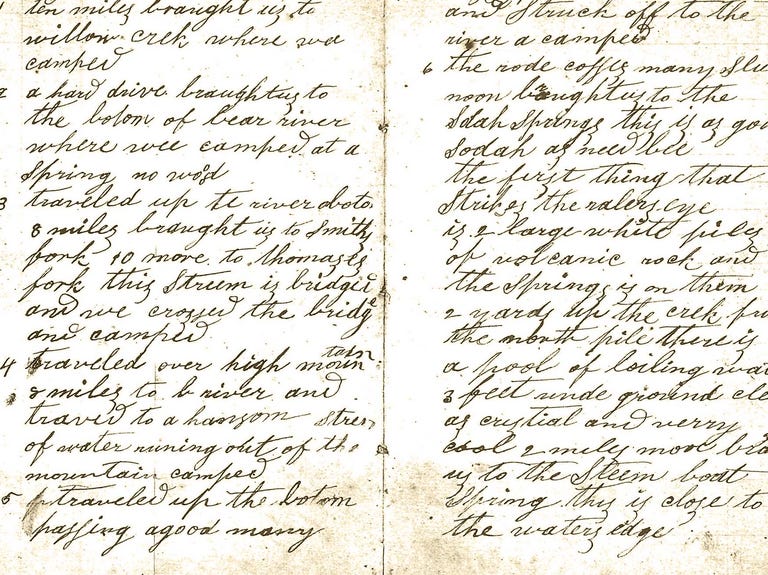

In diaries and recollections left behind by emigrants who took the road hunters’ new route and members of the scouting party, there are differing accounts of the events of the latter part of 1846. What is agreed upon is that members of the forward company, including Jesse Applegate, made their way to Fort Hall that August. There, they recruited travelers for their new route and perhaps sold them supplies for the journey. All told, at least 100 wagons, about 500 people, followed their advice and turned south onto the new trail.

Setting out with Levi Scott, a road hunter from the Applegate team, as a guide, they had no idea that some portions of the trail hadn’t been improved. In his journal and letters written later, Scott recounts being surprised by the lack of improvements and the struggle he and the other men in the train faced each day to clear the road and get the group over the mountains before winter. It made for incredibly slow going. Before long, everything that could go wrong would.

First, the Indigenous people whose lands the road traversed launched a justified campaign of harassment in protest of this encroachment on their territory. Next, the sparse vegetation of the rocky terrain proved too thin to graze the cattle. Then, abnormally heavy rains and record snowfall blanketed the region. Creek beds that had been dry when the road hunters first passed now surged with water, and the ground turned to slick mud, miring oxen, wagons, and people. Then bitter cold and high winds descended, mounting the snow into massive, impassable drifts. Supplies and energy ran low. Livestock froze; wagons had to be abandoned. Finally, the train stopped making any progress at all. They were stranded.

Some people, trappers and scouts more familiar with the terrain and unencumbered by children, livestock, or possessions, made their way into the Willamette Valley. When they informed the people there of the disaster unfolding in the mountains, several rescue attempts were undertaken, one led by the Applegates. In the end, many completed the journey, though some on foot with only the few possessions they could carry. Others didn’t survive.

Those who did survive turned on the road hunters, the Applegates most of all, accusing them in newspapers and pamphlets of being grifters and road pirates. Some even insisted that the men had known all along the company would be stranded and had lured them onto the road anyway.

One member of the train was especially vocal. Jesse Quinn Thornton, a wealthy lawyer and acknowledged peevish grump who had lost all his belongings (including, as he itemized, a medicine chest, cut-glass bottles, and a cast-steel spade), grabbed onto the issue and wouldn’t let go. He focused his rage on the Applegates, who he claimed were the responsible parties. For months, he published piece after piece in the papers, decrying Jesse Applegate, his team, and “that damnable Applegate Road.”

That the road was considered a failure, that lives had been lost, and that the Applegates were considered to blame pained the brothers and compounded the loss of their own boys to the northern route. Their intentions had been motivated by grief, a heartfelt conviction that no other family should lose a loved one on the way to Oregon. They were distressed that their path had caused such suffering and loss of human life. That anyone would suspect them of ill intent, of grifting, was devastating.

Some of the shine was gone from the Oregon Country. In an 1848 waybill describing the Applegate Route to forthcoming emigrants, Jesse warned new arrivals to retain a milk cow until the end of the journey, as, he said, “the people here are poor and hard hearted.” But even with family back in the Midwest to return to, the Applegates remained, convinced that their fortunes and destinies lay in the West.

Two of the brothers, Lindsay and Jesse, had itchy feet. At first, Lindsay joined the gold rush to the south in California, but he found the conditions and the miners too harsh and left for home, losing most of his lode to grifters and sour deals along the way. When he returned, he and Jesse thought they could capitalize on the gold rush the easy way, by selling supplies to miners headed out to the claims and converting their golden nuggets into watches and jewelry ready for the eastern market. Value-added products, they reasoned, were where the real money was.

As Susan Applegate, a descendant of Charles, explains, they put up the first building at the base of the mining hills in the Rogue Valley. It immediately drew prospectors setting out for their claims. All those wagons and white men brought the attention of the area’s Indigenous people, who had for some time been locked in a war with the federal government and settlers. They made it clear to the Applegates that their building was unwelcome. The status quo was to dig in and hold the land, but the brothers couldn’t stomach it. When the time came and, as Susan Applegate puts it, “arrows were flying past their hats,” they made a run for it back up the valley to their families, burning their fort behind them.

After that, it seemed like Jesse and Lindsay were always doing something new. Lindsay stayed close to his family for a time, operating a toll road, participating in county politics, and, never forgetting that first year’s tragedy, serving as the captain of a volunteer company that protected incoming emigrants along the southern routes. Eventually, he joined the army, hunting down deserters and serving as a so-called special Indian agent during the Rogue River Wars. He proved himself to be a leader like Jesse, commanding his own company. When he returned, he moved his family away from his brothers’ homesteads in the Willamette Valley and reestablished himself near present-day Ashland. Despite his absences, he and his wife, Elizabeth, had 12 children together, 5 of whom would die before their parents, taken by the hardships of the Oregon Country.

Even with the damage done to his reputation by the debacle of the southern road, Jesse stayed in politics, becoming a member of the government commission charged with settling a territorial dispute with the Hudson’s Bay Company. When the issue of the now officially recognized Oregon Territory’s borders was finally settled, he focused his attention closer to home, serving as a justice of the peace and establishing his house in what is now Yoncalla as an official polling location and post office. For a time, he and his wife, Cynthia, ran a general store out of the building. They had at least 12 children as well, though half did not make it to the next century and at least 2 were lost as infants.

For the most part, Jesse’s reputation seemed restored. He was known for maintaining a massive private library and was well respected for his prolific writing on topics political and personal. His writing even earned him a new nickname: the Sage of Yoncalla.

But Jesse was dogged by misfortune. He lost his house and land claim by unwittingly backing a friend who was embezzling government bonds. When his friend’s scheme was discovered, the courts held Jesse liable in a decision that left him deep in debt. After that, he ran cattle with his sons and then his grandsons on someone else’s land until the debt could be repaid. Then, against all his moral directives, one of his daughters married a Southern sympathizer. Unable to tolerate their perspective, Jesse disowned her, a loss he felt as a death. At the end of his life, he is said to have paced the floors at night, unable to sleep, terrorized by visions of death and the people he had lost.

Charles had brokered a tenuous peace with the Indigenous inhabitants who had used the valley for centuries to harvest and process camas root, and they allowed him to reside there for all of his days as a farmer, without fear of violence. On his homestead in Yoncalla, just a little over a mile from Jesse’s old place, Charles constructed a two-story, whitewashed home with ample porches and low interior ceilings. It quickly became a cornerstone of the rapidly growing community despite its unusual layout, which consisted of two living spaces, one for the men of the family and one for the women. If Melinda wanted to speak to her husband, she had to exit her side and enter through his exterior door like any other visitor. Whether this arrangement was her idea or his, no one has ever known. Still, the house stood impressively against the landscape.

The Oregon Country never produced the bounty the brothers had envisioned on their arrival. What successes they did have were often undermined by floods, illness, and the changing population and political landscape. Yoncalla never became a major city, nor did any of the nearby settlements. Toward the end of their lives, when Lindsay moved his family away, the distance and busyness of life caused the brothers and their families to grow apart. Charles died on August 9, 1879, leaving Melinda and 12 of their 16 children to chart their own routes through the Oregon Country.

None of the brothers lived to see what came of the Oregon Country or their southern emigrant road. Jesse died nine years after Charles, and Lindsay followed him a few years after that, in 1892, just as the frontier closed.

The Applegate brothers’ legacy, both good and bad, endures. The house Charles built still stands. It is considered one of the oldest homes in Oregon, and in a credit to his family, it was continuously occupied by his descendants into the 21st century. The controversy surrounding the southern road and the brothers’ role in the tragic events of that first year hounded them to the end of their lives. It, too, carried on into the 21st century, with emigrant descendants on all sides fighting over whose name deserves to be attached to the trail.•

PART FIVE: HISTORY OR OLD GOSSIP? »

Visit altaonline.com/serials to keep reading ‘That Damnable Applegate Road,’ and sign up here for email notifications when each new installment is available.

Ruby McConnell is a writer and geologist who writes about the intersection of the natural world and human experience. She is the author of the critically-acclaimed outdoor series A Woman’s Guide to the Wild and A Girl’s Guide to the Wild and its companion activity book for young adventurers, and Ground Truth: A Geological Survey of a Life, which was a finalist for the 2021 Oregon Book Awards. She lives and writes in the heart of Oregon country. You can almost always find her in the woods. She's on Twitter at @RubyGoneWild.