Deborah A. Miranda begins her “tribal memoir,” Bad Indians, with a declaration. “California,” she writes, “is a story. California is many stories. As Leslie Silko tells us, don’t be fooled by stories! Stories are ‘all we have,’ she says. And it is true. Human beings have no other way of knowing that we exist, or what we have survived, except through the vehicle of story.”

She’s right, of course—story is everything. Without it, we cannot make meaning in the world. And yet, I’m also drawn to the Leslie Marmon Silko admonition: Don’t be fooled by stories, she insists. It’s an important idea, not a corollary exactly but a complication, a reminder that stories cut both ways. They can liberate or imprison us; they can render us visible or erased. Such a tension is a key component of Bad Indians, which is a book of collective and cultural history as much as a set of personal and familial narratives.

This article appears in Issue 25 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

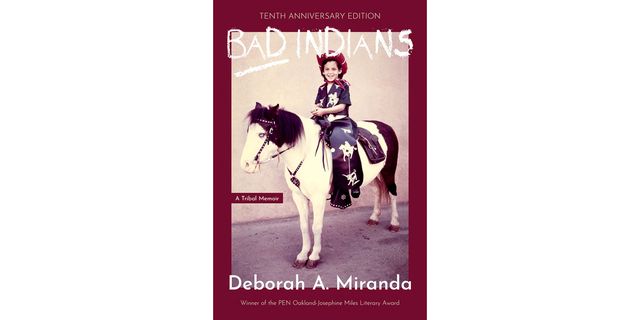

Miranda’s father was Chumash and Esselen, her mother “born and raised in Beverly Hills.” In her introduction, the author writes, “From my mother, the French Huguenots fleeing to the New World to escape religious persecution. English peasants looking for land. Starving Irish trying to outrun famine. Traumatized Sephardic Jews looking for yet another new start.” Opposite this, she juxtaposes a parallel bit of biography: “My father’s genealogy of genocide, smallpox, enslavement, loss of language, religion, culture, health, land, his inheritance of violence and struggle and fear, alcoholism, diabetes, poverty.” The texts are arranged in columns on a single page and superimposed over a black-and-white photograph of Miranda as a child, with her parents on a beach.

Throughout Bad Indians, Miranda develops an increasingly complex set of associations in which the history of California’s Indigenous peoples informs that of her family. In perhaps her most stunning reclamation, she creates “a very late fourth grade project”: the Mission Unit. The result is as moving as it is disturbing, written in first-person plural, from the perspective of Mission Indians.

That Miranda’s ancestors were once among this cohort, forcibly relocated by the Spanish in the late-18th and early-19th centuries, is an essential element of the book. Equally so is her framing, which internalizes the torture and the genocide with wicked knowingness. “Due to their animal-like natures,” she notes, condemning the colonizers by appearing to write from within their narrative, “California Indians often made mistakes or misbehaved even when they had been told the rules.” The effect is to highlight the hypocrisies and abuses of the missions, and also the shame.

Throughout Bad Indians, Miranda employs an array of strategies: writing letters and reproducing images, sharing poems and documents. It’s all a way to create territory for the many voices that have been effaced. The point is to explore a larger story, deeper and more diffuse. This is why it must be shared and heard.•