When I was in fourth grade, I made a replica of a mission out of cardboard and plaster of paris—Mission Santa Inés, to be exact. I don’t remember what the teacher told us in connection with the mission, only that the water of the fountain was of blue gel toothpaste and that my best friend’s mission replica was better than mine. Offsetting that, however, I also recall my father, a new immigrant with a strong interest in spirituality, taking me to powwows on a few different occasions and me having many questions.

As a child, I didn’t have any way of figuring out which of the different competing stories of California to which I was exposed were factually true, but the pattern I could readily perceive, though not articulate in these terms, was that something situational and emotional, rather than essential, was going on: the powerful often avoided discomfort, the broken complacency that came with spending hours listening to other people’s painful realities—and simply made up their own story.

As Stanford social psychologist Jennifer L. Eberhardt writes in Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do, children become cognizant of inequality early on, but based on a tendency to want to believe the world is fair, they grow biased toward those from a high-status group, eventually becoming inured to inequality. Researchers found that when the group influential in creating structural inequality was identified, however, children became less biased in favor of the group who created and implemented the structure. In Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir, the November California Book Club pick, Deborah A. Miranda rightly insists on putting together the voices of her people and a critique of the mythology that required them to submit to an unequal structure, even in the telling of their own stories.

At top of mind, for her, is the political function rather than the aesthetic pleasures of mythologies, propaganda, personal stories, and history. She explains, “Who tells a story is a mighty piece of information for the listeners; you must know what that storyteller has at stake. Demanding to know who is telling your story means asking, ‘Who is inventing me, for what purpose, with what intentions?’” Who does it serve to propagate the myth that missions were good?

Mirroring the brutality of the missions is the intensity with which Miranda conveys the story of her own parents, who are presented, in a sense, as a marriage of two different stories of California. She sets out the desire and opposition clearly from the start: “Miche and Al: colonizer and Indian; European and Indigenous; nominal Christian and lapsed Catholic; once-good girl and twice-bad boy. Heaven on earth, and hell, too.”

There is a mythological quality, too, to her description of her mother: “She was beautiful, on fire with suicidal depression, desperate for love.” But the paragraph progresses to something grittier: “Midgie used alcohol and heroin to dull the visceral pain, speed to get up the next morning and get my half-siblings off to school.” There’s a feeling of rapture again with Al’s “half-wondering” tone as he acknowledges that Midgie gave up heroin for him. Yet, her father, as she tells it, was far from perfect. Miranda observes, “No wonder Midgie could give up heroin for my father: she always went for the most destructive drug she could find.” With these intense, poetic passages about her parents, Miranda preserves a fascinating mystique around a tender story of her parents’ romance while also preparing us for the darkness of her father’s violence—his flogging of his small son, which she frames as an imitation of the abusive tactics of imperialists.

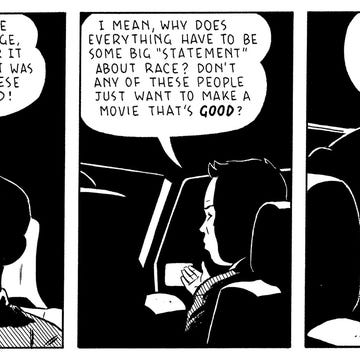

I thought of Miranda’s book while watching Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of David Grann’s superb history Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI. In adapting Grann’s work to the screen, Scorsese presents a Hitchcockian plot that requires a balance of close-ups of a mixed marriage, like Miranda’s parents’, between Mollie and Ernest, an Osage woman and a white man. The marriage is against the beauty of a panoramic landscape and part of a tragic piece of history. Oil had been found under Osage territory, and as a result of the mineral rights that accrued to the Osage, tribal members had become strikingly wealthy by the 1920s. White men determined to inherit all that wealth began poisoning and killing the Osage.

Wisely, as a filmmaker rather than an author, Scorsese focuses a little less attention on the social, historical detail that Grann elucidates and more on the marriage. Unlike Miranda’s parents, desire was not a driving force, at least as Scorsese and Grann portray it—rather, white men’s cruel greed is. You can’t help but feel, while watching it, Scorsese’s effort to remove bias or avoid a false both-sides approach. He focuses on the hideous dynamics of resentment and the turmoil that Ernest feels but at no point lets him and his people off the hook. In this way, Scorsese makes the injustice and betrayal of the Osage easier for us to grasp and refuses any sort of mythologizing that would allow us to indulge in bias against them for failure to pinpoint the villains.

Scorsese left me feeling continued, deep admiration for his aesthetics and his refusal to engage in both-sides-ism by softening the violence done as well. However, in the process of fitting the real-life story of bigotry and brutality into a recognizable dramatic structure for the screen, other aspects of Mollie’s life, and the lives of her mixed children—who must have felt complex emotions about their parents’ dynamic—are not presented. Scorsese also elides the warmth and ordinariness the Osage were robbed of. Their losses would hurt us even more if smaller moments of their lives and well-being, separate from the white men, were juxtaposed against the vile behavior by which they were victimized. Perhaps that would have been too complicated an account for an already long movie, but sometimes I wonder if it’s easier to tell a tale with a perfectly focused narrative arc when you’re relating a story from outside it.

Miranda’s storytelling in Bad Indians is spiritedly multifarious, by contrast. Rightly, since the genocide of California Indians robbed them of well-documented stories like the story Grann tells, which the FBI put together of Ernest and his people, Miranda’s book assumes that identity is not something with a fixed Manichaean essence but a story more fluidly made and remade, a glittering composite, a quality that the law cannot countenance.

To that end, she adopts a range of forms—oral history, memoir letters, satire, and school lessons—as if she’s bringing us along on her journey to find the right form to express the many dimensions of her mixed-family’s history. The section “Teheyapami Achiska: Home 1961–Present,” which features her own story, is particularly compelling and calls to mind her poetry. Take, for instance, when she tells us about the aftermath of her mother’s friend raping her when she was seven: “There are some things I can never do without thinking of Buddy. Braid my hair. Put on a swimming suit. See apple orchards, hear the buzz of bees and yellow jackets when the fruit falls to the earth, bruised.” How sensory the experience was, the irony of such pleasures existing when something so brutal is occurring.

Sometimes, with parenting, you relive your own childhood alongside the childhood you observe your children experience. For Miranda, then, memories of the rape return full force to her when her daughter is seven: “I begin to have bad dreams. Knives. Bees. Screams that are unheard. I feel something coming unwrapped, coming loose, unleashed inside me.” And yet, in her reconciliation is beauty: “The sun raises, breaches heavy clouds. We call this sapphire light ‘dawn,’ but what do we know? Where is the foggy edge between then and now? Maybe it is the difference between inner and outer worlds. I’m remembering the day my anger transformed like molten silver into a blinking nova that I learned to call desire.” The imagery of an interior experience is both gorgeous and surprising: silver into a new star.

Miranda’s aesthetic sensibility, then, is not one of domination, not one that brings us to an all-powerful climax but a place of searching for and cobbling together truths. She brings to life the consequences of a violent bias against California Indian stories: the effect of her accumulation of forms is to suggest the psychological difficulty of containing a true, single story with a dramatic structure (like the one Scorsese deftly employs), out of materials and voices deliberately made scant by powerful, violence-wielding outsiders.

And so, she expresses her philosophy of storytelling: “Sometimes something is so badly broken you cannot recreate its original shape at all. If you try, you create a deformed, imperfect image of what you’ve lost.… As long as you’re attempting to recreate, you are doomed to fail! I am beginning to realize that when something is that broken, more useful and beautiful results can come from using the pieces to construct a mosaic.”•

Join us on November 16 at 5 p.m., when Miranda will appear in conversation with special guest Cutcha Risling Baldy and California Book Club host John Freeman to discuss Bad Indians. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

ORGANIC INTELLIGENCE

Writer and professor Karin Spirn argues that the content and form of Miranda’s hybrid memoir and history serve as an alternative path to teaching students the essay form, which is, in its existing shape, easily replicated by ChatGPT. —Alta

WHY I WRITE

Miranda writes a powerful explanation of her process in writing Bad Indians, explaining that it was guided by the force of ancestral survival. —Alta

QUEER ERASURES

Critic Lorraine Berry reviews Justin Torres’s Blackouts, writing that Torres’s “sensitivity to language and his richly drawn characters are incandescent on the page.” —Alta

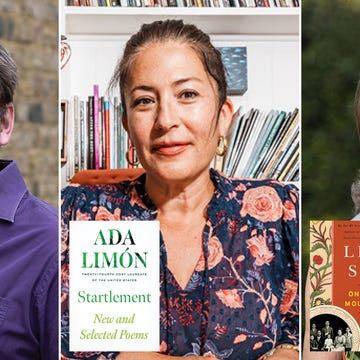

NOVEMBER RELEASES

Here are 11 titles by authors of the West that we’re excited about. They include prior CBC author Michael Connelly’s Resurrection Walk, E.J. Koh’s The Liberators, and Critical Hits: Writers Playing Video Games, which is edited by Carmen Maria Machado and J. Robert Lennon. —Alta

BOUND TOGETHER

Explore Alta Journal’s guide to the best titles that focus on the West by our contributors. —Alta

TELLING AN UNTOLD STORY

Michelle Kicherer writes about Oakland-based author Susan Kiyo Ito’s memoir, I Would Meet You Anywhere, which relates Ito’s journey, as an adoptee, to understand her origin story. Kicherer calls it a “raw and compassionately told story.” —San Francisco Chronicle

Alta’s California Book Club email newsletter is published weekly. Sign up for free and you also will receive four custom-designed bookplates.