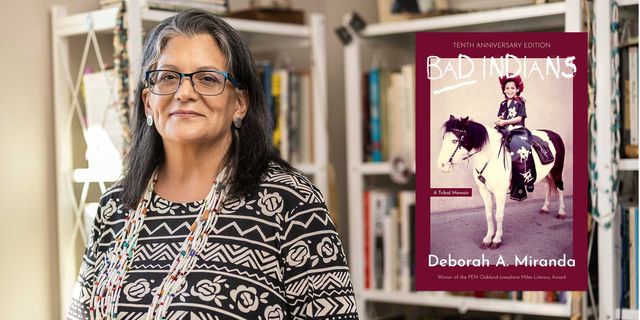

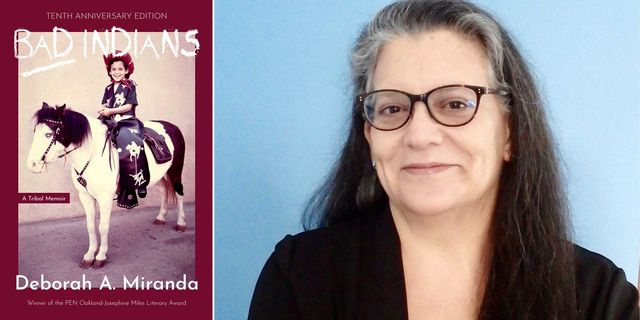

It is so beautiful. It is an offering. It is a workshop. It is a gift to us all,” host John Freeman said of Deborah A. Miranda’s Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir, the book under discussion at the November California Book Club meeting. He commented that one of the earliest scenes of the book features Miranda running into a girl who is in the middle of the fourth-grade California mission project, which Miranda critiques in the book, and is shocked to find herself face-to-face with an actual Indian. Freeman said, “I found it really powerful the way that you decided that rather than say to people who had been participating in that project, ‘Hey, you’re wrong,’ you invite them into your own project.” He asked Miranda how she created such an interactive text.

Miranda said, “The fact that I was doing research on communities that were really only represented by fragments in various archives had a lot to do with the fact that the book turned into this hybrid project that blends so many different genres.” She worried that nobody would ever publish it because it wasn’t a straightforward narrative, but she decided to follow what the stories needed. “Sometimes when you have fragments, you’re never going to have the whole thing. You’re never going to get…all the pieces you need to make something whole again. And that’s pretty much what happened to California Indians. There’s not a whole culture waiting to be returned to us or waiting for us to find in the archives. When you lose 90 percent of your population in 100 years, that’s like losing a million libraries full of information.” She realized that she needed to use the fragments she had but also let the gaps speak. “Let the absences speak and not try to sort of create a whole culture that I couldn’t even begin to imagine,” she said.

Freeman noted that Bad Indians is full of people like Ohlone ethnologist Isabel Meadows and Miranda’s ancestors, whom Miranda encountered in the archives early in her research. He asked, “Was there a moment when you were in the stacks at UCLA…and you said, ‘Holy—insert word—that’s my great-, great-, great-, great-, great-, great-, great-grandfather’?” Miranda responded affirmatively and told of coming across a story in which Meadows mentions a fox wandering through Carmel that was sick. Tomás Miranda ran and shot it. They planned to make it into a purse to carry sacred things. “That was my grandfather’s father, Tomás Miranda, and to see him in that context and to know that he was a member of that community—it was a moment of belonging, a moment of saying, Yeah I’m here. I’m in this story as well.”

Special guest Cutcha Risling Baldy, the author of We Are Dancing for You: Native Feminisms and the Revitalization of Women’s Coming-of-Age Ceremonies, joined the conversation. She’d first encountered Bad Indians in graduate school. After she and others read it—after engaging with many heavy, scholarly texts—two of the other students looked at her and said, “Finally! Finally the book we’ve been looking for as Native women trying to get our PhDs and do this work of writing and telling stories.” Risling Baldy said that they “felt this great sense of relief. That there was this work there that could model for us that there was something else that we could do to tell these stories about our peoples and our histories and our ancestors.”

Risling Baldy noted that she’s on sabbatical and that among people who do this kind of work, she’s been talking about what it means to be a “bad Indian.” “When we talk about what it means to be a bad Indian,” Risling Baldy elaborated, “I really think about the people that we work with, the people that we know, and how I would call them bad Indians. I’d be like, ‘You’re a bad Indian because you’re constantly coming in and saying no to the settler state.’ And you’re saying, ‘No, I’m not going to do it this way.’” She asked Miranda what it really meant to be a bad Indian, then and today.

Miranda said that during mission times, the padres used the phrase “bad Indian” over and over in their notes when talking about someone who kept stealing cattle or someone who wouldn’t stay with her husband and who slept around. “Bad Indians were people who refused to submit in some important way to the Spanish agenda and did not want to be ‘converted’ or ‘saved.’ They were perfectly content being who they were.”

Miranda felt that she was there writing the book because of the Indians who were bad, who had resisted unjust laws and “lived long enough to have someone I could be descended from, which was not easy when the age expectancy of a child on the missions was seven years old, so living to adulthood and having a child sometimes was as far as my family tree went.” When she explained to her son that their ancestors were “bad Indians,” he said, “Our ancestors weren’t just bad Indians. They were badass.” She thought, “That’s it. That’s what I’m trying to say. They had an incredible instinct for survival, and they had attitude. And that was what saved us.”•

Join us on December 21 at 5 p.m., when author Carribean Fragoza will appear in conversation with California Book Club host John Freeman and a special guest to discuss Eat the Mouth That Feeds You. Register for the Zoom conversation here.