When I was a boy, the Sisters of St. Joseph encouraged students at St. Bernard Catholic School in Bellflower to head their work with the cipher AMDG—Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam, or “to the greater glory of God.” I began book reports and exercises in cursive letters with AMDG. This other language—a different music—hung over my schoolwork, half rhyming at the top of each page.

Four years of Latin in high school, Caesar’s Bellum Gallicum and Virgil’s Aeneid—studying the literature of war in a time of war: conventional, nuclear, and Cold, all the wars into which I had been conscripted at birth. I had a year of Russian in high school because Russian-language proficiency—subsidized by the U.S. Department of Education—was a weapon. But I failed to learn the crooked Russian alphabet or the “hard sounds” and “soft sounds” of Russian words. I can still recite the first verse of “Katyusha”—a soldier’s farewell and the nickname of a Soviet rocket launcher.

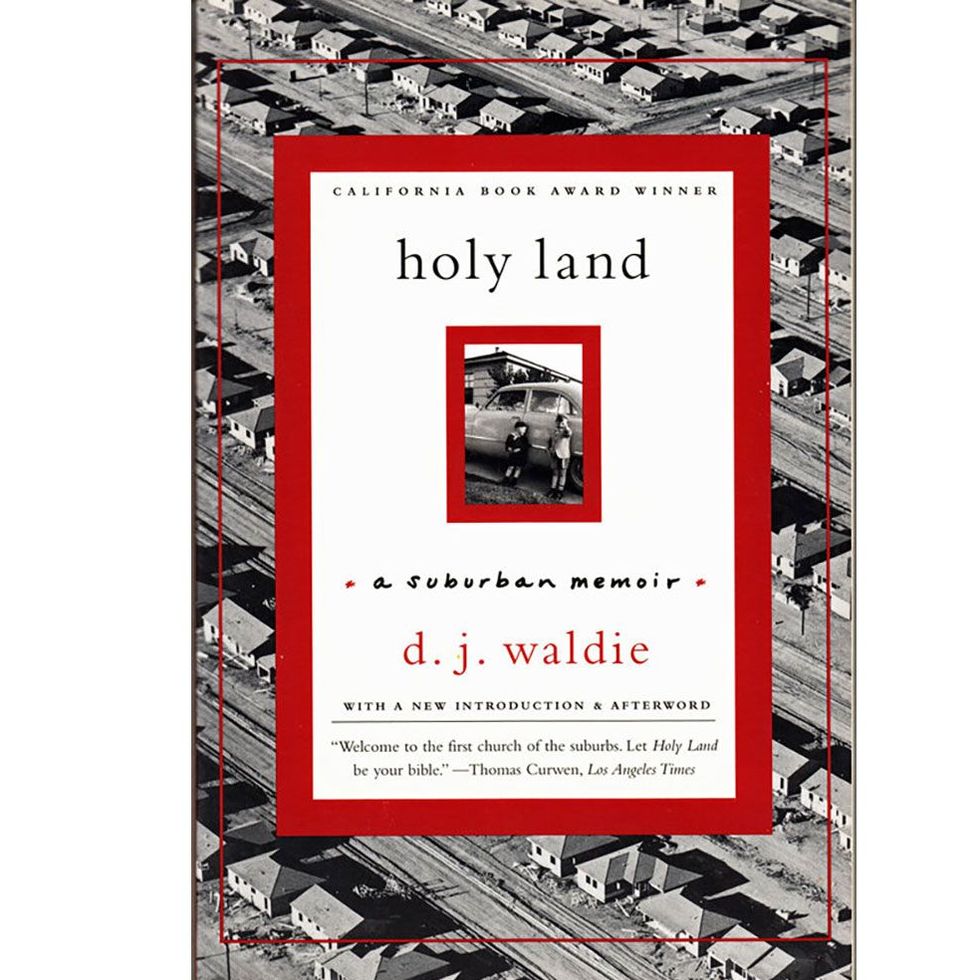

This article appears in Issue 26 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

In 1972, as a miserable graduate student in comparative literature, I walked into the library at UC Irvine to borrow a copy of an untranslatable French poem. It was Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés, not so much a poem in French as a quantity of empty space bounded by words. Twenty years of translating later, I had something with a certain plainness and in American idioms that stared into the limits of poetic language. Mallarmé could have gone further, even to the blank page and silence, but it was “suffisamment, pour ouvrir des yeux.” It was enough, he said, to open some eyes. Including mine.

“It’s all in the ear,” the poet William Carlos Williams told an interviewer toward the end of his life, when speech was growing difficult for him. The work, he added, “must be transcribed to the page from the lips of the poet.” That’s as good an answer as any to Mallarmé’s gorgeous abyss, where words dissolve into the low murmur of waves.

I walk and—it seems inevitable—I write. Charles Dickens walked. So did Virginia Woolf and André Breton and Ray Bradbury (a nondriver like myself) as well as innumerable other writers who knew, like Rebecca Solnit, that “a city is a language…and walking is the act of speaking that language,” as it was for Michel de Certeau, for whom narrative “begins on the ground level, with footsteps.” I walk what I write, and it’s the conjunctions, the ellipses, and the consonances of suburban streets. They’re ordinary, narrow streets where I walk, but the grid of my city opens outward, pointing in many directions. Every intersection is a story that feels as if I’ve just remembered it.

What I write has to have an argument. It has to have things in it to give ideas texture and purchase. It has to sound as though it was spoken just now. It has to know that it’s made of words and that these have backstories and sonorities and their own purposes. It has to have a felt sense of something happening. It has to be in a definite place, a place revealed to be, as Kathleen Stewart stresses, “tentative, charged, overwhelming, and alive.”

The argument is that places matter. What’s remembered there, and who gets to remember? What use is its history? How does a place become a home? I write to know where I am, to put myself in its story, to understand what it’s made of me, and to negotiate a way from the personal to the political. I write about a tragic and lovely place called Los Angeles (not exactly bounded by city limit signs) where the habits of an ordinary life can be made. I’ve been told that Los Angeles is gaudy but inconsequential, a place devoid of authenticity. I’ve learned that it’s just as mortal as me.•