What is Los Angeles? Dreamscape, city of the future. Land of reinvention, of forgetting or of myth. What all this overlooks, of course, is an idea of it as home, as a collection of communities in which humans live. As D. J. Waldie has observed, “clinging to outdated images of Los Angeles, too many Angelenos avoid encountering the city as a real place. The results are often tragic. Denied access to the sacred ordinariness in our stories and barred from cherished locales mapped on a skin of memories, talk about Los Angeles turns to exceptionalism.”

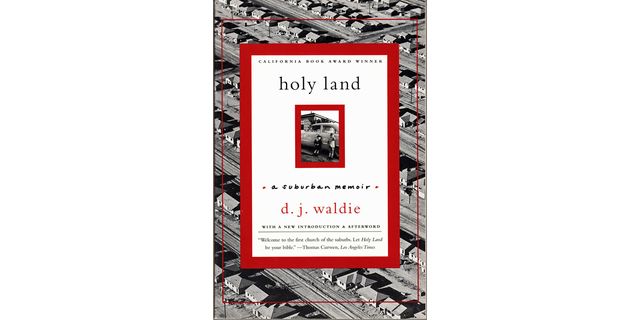

Waldie has been a quintessential Southern California voice since the publication of Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir, in 1996. There, in 316 brief and careful chapters, he excavates the idea of sacred ordinariness and what it means. It’s a transformative concept, not least because before Waldie came around, no one had thought to frame the region through such a filter. Even James M. Cain’s 1933 essay “Paradise,” the book’s closest precursor, can’t help but caricature or exoticize on occasion. Waldie never does anything of the sort.

This article appears in Issue 26 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

In part, that’s because the Los Angeles Holy Land surveys is Greater Los Angeles: not the city but the suburbs, as the subtitle suggests. Equally important, it’s because the book is steeped in place. Waldie still lives in the house where he was born in 1948 in the suburb of Lakewood, developed after the end of World War II. This is not the Southern California of glitz and glamour, but rather of the middle class. “From age six to thirteen,” Waldie recalls, “I spent part of nearly every day and nearly all summer in the company of my brother and other boys who lived in houses like mine.

“The character of those seven years is what makes a suburban childhood seem like an entire life.”

It’s easy to minimize what Waldie is doing; there is nothing exceptional or dramatic in what he writes. Except, of course, there is: both the human life of Lakewood and the geological history that undergirds it. “As late as 1914,” he notes, “the runoff from foothill canyons was allowed to flow unchecked into the vague rivers of the coastal plain. They dropped new sand and clay over soil deposited by older rivers during the late Pleistocene.” The result is “mediocre land for wheat or barley, but…good enough for growing sugar beets.”

Waldie’s brilliance resides in this low-key approach. He’s a miniaturist who gets maximum effects. There’s not a section in Holy Land longer than a couple of paragraphs, and yet the collage adds up to something comprehensive in an unexpected sense. Even more, the book evokes how it feels to live in Southern California, where the larger story often remains inaccessible.

Sacred ordinariness, in other words, which remains Holy Land’s most essential attribute.•