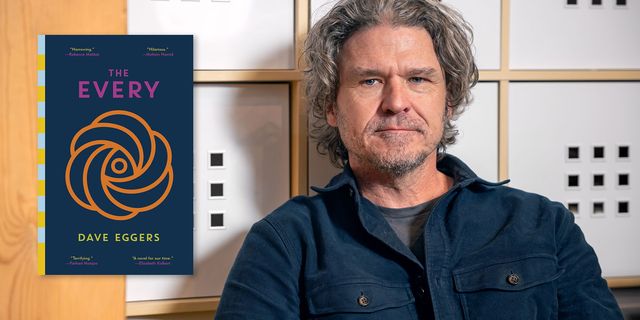

Everything can be quantified in The Every, Dave Eggers’s terrifying, devilishly funny surveillance-capitalism novel about a San Francisco–based tech company that feels like a pumped-up, unholy mash-up of Amazon, Apple, and Facebook (in the book’s universe, the Every is the result of a merger between a company based on Amazon and the Google-like outfit at the center of a previous Eggers novel, 2013’s The Circle). Digital “ovals,” tracking bracelets mandated by insurers and governments alike, tell people how much they should be laughing every day and reward speakers for using 10-dollar words, even when the usage makes no sense. Popular apps tell users how long they are likely to live and how friendly the friend to whom they’re speaking really is. Everyone is always on camera. All travel is discouraged, for the sake of the environment, of course. The policies have all put into place for ostensibly enlightened reasons—safety, sensitivity, self-improvement—but the end result is a sort of soft-shoe dystopia, parts of which should be recognizable to anyone living in the 21st century.

Eggers’s targets are many, most of them dealing in some way with the dehumanizing and infantilizing of American society. But he saves some of his sharpest barbs for a subject near and dear to his heart: the devaluing of books and literacy. Eggers’s San Francisco–based nonprofit 826 Valencia seeks to empower under-resourced children to write. He approaches reading and writing as sacred elements of the human experience. So when the Every chips away at spontaneity, risk, and the capacity to make excursions and mistakes, the experience of reading as we know it sits squarely in its crosshairs.

We see this primarily in chapter 18, when Delaney, a young woman who takes a job at the Every in the hope of destroying it from within, pays a visit to TellTale, a department that specializes in streamlining the way we tell and consume stories. TellTale was created by an Every honcho who, as Delaney’s guide explains, “read some fiction novels?” He found the experience inefficient, and so he set out to create an ideal reading experience, engineered to maximize time and avoid chance. The results are enough to make bibliophiles laugh between their tears.

“Obviously paper books provide no useful data and should be abolished,” explains Delaney’s guide, before handing her off to the current head of TellTale, Alessandro. Once an aspiring comp-lit professor, Alessandro saw the Every light and switched sides. He has data that shows that many readers just don’t cotton to mean or unlikable characters. He has ascertained that out of 2,000 readers who started Jane Eyre, only 188 finished it. But wait—there’s more. Most of those who put the book down did so around page 177, with the introduction of Grace Poole, Bertha Mason’s drunken caretaker at Thornfield. She’s not nice. So let’s just get rid of her. Turns out the Every has developed a “pretty simple code for turning an unlikable character into, like, your favorite person.” Alessandro continues: “The main thing is that the main character should behave the way you want them to, and do what you want them to do.”

There’s a lot to unpack here. Let’s focus on the playful mischief with which Eggers treats a current scourge brought about by the decline in critical thinking: the lazy conflation of depiction with endorsement. Literature, drama, and film are laden with characters and behavior you might not want to associate with in real life. This is why we have villains, who are usually the most interesting characters in any given story. (Remember: Milton gave Satan the best lines in Paradise Lost.) The task of the narrative arts is to reflect the whole of humanity, not cheerlead for the nice people. And yet there’s an increasing din among those who willfully misread the dramatization of evil as a reflection of the storyteller’s character, or as an endorsement of bad behavior—essentially pounding the humanities into the banalities. In demonstrating the Every’s seemingly benign assault on life’s human factor, Eggers makes a powerful argument for how that factor infuses books.

Like so much at the Every, it all comes down to data. The data, according to Alessandro, suggests that “no book should be over 500 pages, and if it is over 500, we found that the absolute limit is 577.” (It’s no accident that The Every is exactly 577 pages long.) Data also includes aggregation, of which the Every is quite fond. Here, Eggers has some fun at the expense of companies like IMDb and Rotten Tomatoes, which chew up numbers and spit out scores. But that’s kid stuff within these pages. As Alessandro explains, “The aggregates worked so well that they quickly moved from movies into painting, dance, sculpture, poetry. I mean, you should have seen how low sonnets scored! That’s why you don’t see those taught so much anymore.” (Delaney, playing along: “Sonnet? What’s a sonnet?”)

No bard, it seems, is safe. With the likes of Iago, Macbeth, and Richard III lurking in his pages, Shakespeare would surely get dinged on the likability scale as well. As with everything at the Every, this is all couched as a social good. TellTale also has a program whose AI “helps” novelists by writing “the parts no one reads anyway—the interstitial stuff.” Because, as Alessandro puts it, “if we value humans, we save them from the mundane tasks.” Like, for example, reading.

Throughout these pages, and particularly in this chapter, we see that Eggers values the journey as much as the destination. He understands that the so-called interstitial stuff is what keeps everything from becoming a climax, and therefore what makes a climax special. Similarly, he recognizes the importance of life’s small, quiet moments, which, in their own way, can lead to adventure, or at the least essential discursion. Such adventures and discursions are at grave risk in the world of The Every. Reading with hunger and curiosity, Eggers suggests, can help keep them alive.•

Join us on February 15 at 5 p.m. Pacific, when Eggers will appear in conversation with California Book Club host John Freeman and special guest Caterina Fake to discuss The Every. Register for the Zoom conversation here.