What is beautiful here?” asks D. J. Waldie early in Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir, his spare, meditative account of life in Lakewood, California, a modest post–World War II suburb sandwiched in the sprawl of South Los Angeles and east Anaheim. It’s a question and a provocation—a prompt for us to reflect on the response we expect. Do we anticipate scorn—a “nothing”—confirmation of the not-quite-urban’s bland ugliness? Or something softer, more lyrical, a revelation of the lush nature teeming even in the Golden State’s most unassuming corners? Waldie’s answer gives us neither—or maybe both at once. “The calling of a mourning dove, and others answering from yard to yard,” he reflects. “Perhaps this is the only thing beautiful here.”

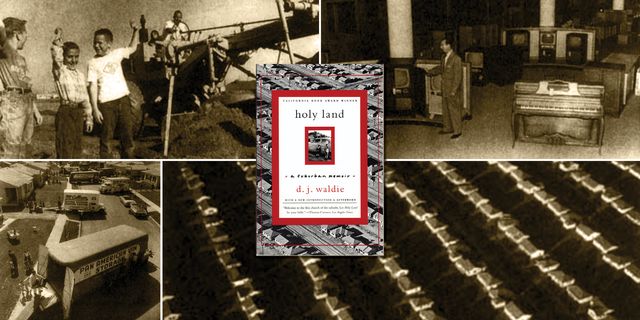

Part memoir, part history, Holy Land, first published in 1996 and reissued in 2005, mines unadorned facts for the kind of prismatic evocation more typical of the figurative. Its 316 compact sections braid recollections of a Catholic tract home childhood with vignettes of Lakewood residents and dispassionate specifics about the suburb’s genesis. Pulsing throughout, however, is the sense that Waldie, like the 20th-century California chroniclers Joan Didion and Charles Bukowski before him, is participating in a larger project of wary elucidation, a rejoinder to those who might be too ready to dismiss SoCal—or, worse, conflate it with the glossy superficiality of Hollywood. Like so much writing on the American West, Holy Land is a project of explanation and self-definition that illuminates what its subjects aren’t as much as what they are.

Fittingly, Didion was one of Holy Land’s first champions. She quoted from an early version of the work in a 1993 piece she wrote for the New Yorker about the Spur Posse, a group of Lakewood teens who were arrested but never charged for a series of rapes linked to a competitive high school sex club and who became a ’90s emblem of amorality among suburban youth. It’s easy to see why Didion, always tuned in to the California frequency buzzing through the American zeitgeist, was drawn to the topic. So much of her writing provides a kind of anthropological translation of a strange, vast, heterogenous state, less for the people who live there than for an implied audience of aspirational and actual New Yorkers, comfortable with their erudite provincialism but eager for vicarious exposure to what lies beyond.

But if Waldie might be classified as one of Didion’s heirs, similarly interested in cracking open California’s shiny mythology, Holy Land feels—importantly—less like something written for people elsewhere. Unlike Didion, Waldie speaks to us from within Lakewood itself, now the sole resident of the very 957-square-foot house he grew up in, possessed of a day job at Lakewood City Hall that allows him to know the recondite goings-on of the town’s residents. In Holy Land’s early sections, the narration slides between first, second, and third person, sometimes explanatory, sometimes interrogatory. The conversation Waldie seems to be having with a version of himself blurs into one he’s having with us. At one point, drawing a connection between his father’s “indifferent” generosity and the pragmatic production of Lakewood’s houses, both like “product[s]…from a conveyor belt,” he levies an accusation: “You are mistaken if you consider this a criticism, either of my father or the houses.” This “you” places us on the outside, cautioning us against the assumptions we may be tempted to import into the suburb’s story. Only pages later, however, we are casually invited inside. “You leave the space between the houses uncrossed. You rarely go across the street, which is forty feet wide,” Waldie writes. “It is as if each house on your block stood on its own enchanted island, fifty feet by one hundred feet long.” This is an inclusive “you,” pulling us in, inviting us to imagine Waldie’s home as our own.

Holy Land’s oscillation between exclusion and inclusion is appropriate for a portrait of the suburbs, which, as Waldie reminds us, are as much instruments of segregation as they are a means for the marginalized to remake themselves as middle class. In a paradigmatic encapsulation of this Janus-faced quality, Waldie notes that the three Jewish businessmen largely responsible for the version of Lakewood known today would have been excluded from living in its first iteration. Deed covenants explicitly prohibited the sale of lots to “Negroes, Mexicans, and Jews,” which, in that hoariest of ironies, helped the white Catholics and Dust Bowl refugees who bought there feel as though they’d made it.

These facts aren’t so much in tension with as of a piece with what Waldie reveres about his home: its capacity to dignify lives of modest means, creating unexpected affinities through material conditions. “There was very little that distinguished any of us living here,” he recalls. “We lived in what we were told was a good neighborhood.… Our parents were anxious to do what was expected of them, even when the expectation was not altogether clear.” Much like the experience of California itself, it proves impossible to peel apart what people feel about the suburbs from what they are. Built to be anodyne, they seem to absorb our fantasies and antipathies, their stucco and wood sodden and warping with our visions of what a good life looks like. In Waldie’s account, the California suburbs make anthropologists of all who live there, holding their residents at a distance, welcoming them in, encouraging both their voyeurism and their tolerance for being observed. The numbers, facts, and statistics Waldie piles alongside memories of watching his parents age and playing with the boys on his block don’t so much counteract all that we think we know about the suburbs as ask us to consider how those who live there might engage in telling and retelling those same stories, even as they live out a specificity that transcends them.

Perhaps, then, we should think of Waldie less as the heir of Didion than as her quietly recalcitrant offspring, both borrowing from and chafing against a way of thinking about California that her work helped to instill. Like her version of her home state, his Lakewood is endlessly engaged in the work of asserting itself as deeply, definitively American and unyieldingly distinctive all at once, calibrated to that West Coast frequency Didion loved to amplify. But there is something more in Holy Land too. From within his small house in his spreading SoCal neighborhood, Waldie tunes in to the other sundry sounds too often drowned out—those calls of mourning doves, those voices heard through open windows just feet away, familiar and strange, each carried on a frequency all its own.•

Join us on January 18 at 5 p.m., when Waldie will appear in conversation with California Book Club host John Freeman and special guest Lawrence Weschler to discuss Holy Land: A Suburban Memoir. Register for the Zoom conversation here.

Previously, we incorrectly stated that Holy Land had fallen out of print. Please purchase the book directly from the publisher.