Over the course of 30 raucous—make that ass-kicking—years, Vanity Fair’s mix of consequential journalism and bold-faced names pulled in millions of dollars. And with the exception of Jann Wenner’s Rolling Stone, the VF edited by Tina Brown from 1984 to 1992 and then by Graydon Carter from 1992 to 2017 dominated the media conversation. Both editors wrote about how they did it—Tina in The Vanity Fair Diaries and now Graydon with When the Going Was Good: An Editor’s Adventures During the Last Golden Age of Magazines. I doubt either will particularly like being in the same sentence, but there are occupational hazards.

Graydon and I were introduced by Carl Navarre, owner of Atlantic Monthly Press, at a dinner in 1985 at Carl’s Upper East Side co-op, both of us unaware that the other was after Carl, also a Coca-Cola bottling heir, to invest in our respective magazine startups—his Spy and my Smart. We both knew Carl through Atlantic’s editorial director, Gary Fisketjon, and Jay McInerney, whose novel Bright Lights, Big City brilliantly rounded up the details of that particularly berserk decade. Graydon received $500,000 for Spy; I secured $5,000 for Smart. I don’t hold any of that against Carl or Graydon. Spy was a better idea, and there is a bigger picture to reckon with now that the future of magazines looks like no future at all. To understand what that means, you have to know what actually happened to magazines since that time, and that’s what Graydon is giving us. I didn’t know, for example, about that half million bucks until I read When the Going Was Good. Which brings me to what else I didn’t know about Graydon, which is plenty.

Our generation of editors was profoundly influenced by an earlier so-called golden age defined in the 1960s by Harold Hayes’s Esquire and Clay Felker’s New York magazine. Graydon’s era was richer, and his writing is so candid and self-revealing that it would feel stilted to call him anything but Graydon—like it would the other mononymous editors of our generation: Jann, Tina, and Anna. However, as audacious and inspiring as their careers have been, the line stops with Graydon. The title “editor in chief” (rhymes with “great barrier reef”) used to mean first-class everything. Those days are gone forever, like in Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi.”

Graydon and I became friends, and have even edited each other. I’m in Graydon’s memoir (page 118), and—full disclosure—he blurbed mine, The Accidental Life: An Editor’s Notes on Writing and Writers. I could recuse myself to avoid the logrolling that Graydon made biting fun of in Spy, but our careers have a telling symmetry. Graydon arrived at Time from Canada in the late 1970s, and a few years later I landed at Newsweek (by way of many places, but starting in California), both of us hicks surrounded by Ivy League overachievers, comically naïve about how the media business actually worked—what power was and what you had to do to get it in an established order built on generations of wealth. It was a steep learning curve. Graydon: “There is nothing more parochial or bland than being a soft, white Anglican kid from Ottawa.”

This article appears in Issue 31 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

It was also so boring between deadlines at Time that Graydon napped at his desk. Transferred to Life, he put together the Letters to the Editor section when weeks would go by without a single submission. Out of desperation, Graydon and a friend, Time writer Kurt Andersen, started working on a fact-based satirical monthly about New York’s celebrity, money, and media. It would be called Spy, after the tabloid magazine Jimmy Stewart worked for in The Philadelphia Story. They raised $1.5 million, including that $500,000 from Navarre, and put Time Inc. in the rearview mirror.

Spy’s caustic profiles and celebrity takedowns tickled every schadenfreude nerve in media culture. Even the graphics were irreverent, with dense, information-packed layouts. Most importantly, Spy’s voice was like catnip. Andersen called it “literate sensationalism.” Graydon wanted “a bemused detachment but witheringly judgmental.” The first issue led with a cover story titled “Jerks: The Ten Most Embarrassing New Yorkers”—influenced by Private Eye in the U.K. and the Mad Magazine and Looney Tunes of the editors’ youth; that is, the approach was more than vaguely anarchic—like smuggling a reporter into the Bohemian Grove disguised as a waiter.

Graydon enlisted the esteemed Felker and Rolling Stone founder Jann as advisers, but those were treacherous times. Without mentioning that he was about to become editor of rival Manhattan, inc., Felker told Graydon that Spy was never going to attract readers, was hopeless, and should be shut down. They never spoke again. Jann was more helpful, suggesting that Spy’s media column focus on the previously unmockable New York Times. The paper’s former feared executive editor and his wife, a ranking editor at Vogue, became “Abe ‘I’m writing as bad as I can’ Rosenthal” and “bosomy dirty book writer Shirley Lord” in Spy’s bridge-burning column by the pseudonymous J.J. Hunsecker—the name of Burt Lancaster’s lethal gossip columnist in Sweet Smell of Success. The most powerful people in the movie business got the same treatment in the Industry, a column written under the pseudonym Celia Brady—a bastardization of the narrator’s name in Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon. CAA head Mike Ovitz and his partner, Ron Meyer, worried they might have to close down the agency after Spy ran its secret client list. A private detective was hired to track down Ms. Brady, whose identity, along with Hunsecker’s, remains a secret.

What fun, except for anyone Spy wrote about; or was it? Nora Ephron told Graydon she’d be relieved when she opened her issue and didn’t find herself but then become slightly vexed that maybe she didn’t matter. When Spy ran a photograph of Jill Krementz, the wife of Kurt Vonnegut, identifying her as “champion namedropper and celebrity photographer,” Kurt called Graydon, hanging up with “If you don’t already have cancer, I hope you get it.” I’m sure Kurt was being funny, but there were many who weren’t kidding at all, like Larry Tisch (who was described as a “churlish dwarf billionaire”). Gore Vidal threatened to sue for being called litigious.

And then there was Donald J. Trump. Needing the money, Graydon had taken a GQ assignment in 1983 to profile Trump “at the beginning of his florid tabloid residency.” “The Donald,” as he was then known, hated the story, especially the detail that his hands looked freakishly small. The “short-fingered vulgarian” became one of Spy’s biggest jokes, and Graydon’s ridicule became the most effective antidote to Trump’s self-puffery and bullying all the way to the 2016 rally. Marco Rubio: “You know what they say about guys with small hands…”

It is hard to overestimate Spy’s impact, but by 1990, it was in trouble financially. It was selling 150,000 copies a month, but cash flow was tenuous and expenses dwarfed original projections. After what Graydon describes as a “long and wrenching conversation” with his partners, it was decided that Spy had to be sold. Graydon landed at the New York Observer, a moribund Upper East Side weekly broadsheet on salmon-colored paper. He embraced the color, laid on some edit moves from Spy, and soon enough the Observer was getting noticed—most importantly by Si Newhouse, the shrewd potentate of Condé Nast, who invited Graydon for a chat at his U.N. Plaza apartment. Graydon walked in making $150,000 and fearing Si would offer him GQ. He walked out with a guaranteed salary of $600,000 and the understanding that he would be the next editor of the New Yorker—to be announced shortly. The morning of the announcement, Vogue editor in chief Anna Wintour called: “Graydon, it’s going to be the other one.” Tina would be going to the New Yorker and Graydon would replace her at Vanity Fair. Si (with Tina’s help) had changed his mind.

Graydon writes that going from the Observer to Vanity Fair was like going from managing a boy band to managing the Metropolitan Opera, but he arrived having spent most of the previous decade ridiculing the magazine. Left-behind Tina allies were bitter and subversive. Advertisers that had been subjects of interest in Spy were livid. The vibe was poisonous. Graydon: “I would have hated me if I was in their place.” Courage was required.

Tina had assigned Norman Mailer to cover the 1992 Democratic National Convention before she left, and Graydon happened to see him on the live coverage from Madison Square Garden. Mailer was sitting in the fancy seats, talking with other celebrities. When the writer filed, Graydon read a pedestrian piece with zero detail from the back rooms or reporting from the convention floor. Bracing himself for Mailer’s wrath, Graydon killed the piece but paid the full $50,000 fee. Learning that Mailer had also been contracted to cover the Republican National Convention in Houston, Graydon canceled the assignment and again paid Mailer’s full price. More astonishing to freelancers everywhere will be that over his 25 years at VF, Graydon always paid in full, never a kill fee—thanks to Si Newhouse.

Si’s support meant everything to Graydon, more than he recognized at the time. Si was building a magazine empire based on quality editorial when, meanwhile, one of the richest and most powerful publishers in the world, Time Inc., was beginning to erode under management increasingly concerned with short-term profits. I don’t think I was naïve about magazines as a business, and at Sports Illustrated I was responsible for editorial budgets of more than $50 million, but I suffered through too many meetings that turned into platitude festivals about building a 21st Century Media Company but were really about saving obsolete business models. The lack of confidence in consumer demand for quality journalism was always the subtext. In retrospect, the autonomy and resources Si gave all his editors in chief—especially at VF, Vogue, and, later, the New Yorker—were why Condé Nast was winning what we all thought of then as the magazine wars. Graydon became very close to Si, who shared details of his life that surprise over and over. I didn’t know, for example, that Si’s life revolved around his pug, Nero, and later, Cicero; or that as a young man he was friends with the loathsome Roy Cohn; or that before Si quit smoking, he took puffs between bites at lunch.

Si didn’t smoke in the shower with his arm outside the curtain like one of Graydon’s favorite writers, Christopher Hitchens, but the two of them come off as well as anyone—and Graydon met everyone. Many of those he writes about (a very, very long list) are defined by their excesses, but Graydon is kind as well as candid about what he thought of them. It was all part of the job, and his writing is not so much a lamination of I-did-this and I-did-that as a shuffle of overlapping characters with lessons to be learned from each.

Spy had often run photos of Ralph Lauren with the words “not actual size” accompanying the caption, mocking his height. At Si’s suggestion, Graydon invited Ralph to lunch to begin negotiating a truce—that eventually became a friendship. A pattern emerges: Graydon took his medicine and made friends. At a Calvin Klein fashion show, he met David Geffen, who was kind and whose acceptance was crucial in those early, fragile days. Ditto Barry Diller and Diane von Furstenberg, and their approval boosted his confidence in the face of constant rumors of Graydon’s imminent firing.

At the same time, the good life at Condé Nast included the best New York restaurants, the Beverly Hills Hotel and Hotel Bel-Air in Los Angeles, Concorde flights (passport photo by Annie Leibovitz), the Connaught in London, the Ritz in Paris, Hotel du Cap in the South of France, suites, room service, drivers everywhere, plus, if he felt like it, an “eyebrow lady” who came to his floor once a month. There was also much secrecy when it came to money, and Graydon dealt directly with Paul Scherer, whose midtown accounting firm had an operations floor the size of a “small ballfield” and only one client: the Newhouse family. One day Mrs. Scherer, Janice, was walking into the Condé Nast building wearing her mink when she was confronted by a small group from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals protesting Vogue’s devotion to fur. “Do you know how many animals had to die for you to wear that coat?” one of them yelled. She stopped and shouted back, “Shut up! Do you know how many animals I had to fuck to get this coat?” This story may be slightly off point from Graydon’s narrative, but the tone is pure Condé Nast at the time. Graydon: “It was hard not to admire this woman.”

Spy was still a recent nightmare in Hollywood, where its coverage had been what New York magazine called “unfettered, delectable brutality.” Making numerous rounds in L.A. to try to patch up relationships, Graydon had encounter after mind-blowing encounter. He visited Sandy Gallin, who was exhausted because his client Michael Jackson wanted a two-hour special on all three major networks without commercial interruption, ending with him sitting on a bench between Liza Minnelli and Liz Taylor, and for Queen Elizabeth to come onstage and knight him on live TV. Of course that’s what the King of Pop wanted. In 1994, Graydon published Maureen Orth’s story that broke the Michael Jackson sexual abuse scandal.

Graydon also met new friends, like superagent Sue Mengers, who was close with Barbra Streisand and tight with Jack Nicholson, who shared her affection for marijuana, which, Graydon writes, “helped, except when it didn’t”—like when they threw a dinner for Graydon but forgot to invite him. But there were lots of dinners, including agent Swifty Lazar’s Oscar watch party where Graydon sat at a bad table and got the idea for a Vanity Fair Oscar party. His grasp of status, power dynamics, and social engineering shines through in what he wanted for the first one: a single room, so no A and B delineation; likewise, an extremely tough invitation but no status gradations once you got there.

From that first Oscar party on, Graydon wrangled the elites both coastal and not, somehow mocking and encouraging at the same time. The next big idea was VF ’s New Establishment, which underlined how corporate elders in three-piece suits were being replaced by tech visionaries, media entrepreneurs, and entertainment geniuses—some of whom didn’t even own ties but had bank accounts that let them laugh at old money. Graydon wanted them to be part of VF, and if you want certain people to read your magazine, write about them. Simpler yet, if you want them to like your magazine, have Annie Leibovitz take their picture in their Gulfstream IV (David Geffen) or on the deck of their 158-foot ketch (Rupert Murdoch). Annie spent five months traveling 30,000 miles for portraits of two dozen members of the New Establishment.

Although writers and photographers were then dimly perceived at many magazines, the better you treated them, the better their work. VF treated them like the stars they were. Graydon tells a story of Annie’s annual negotiation coming down to a $250,000 difference between what her agent demanded and what Condé Nast was willing to pay. “Oh, give it to her,” Si told Graydon. “We don’t want to nickel-and-dime them.” Dominick Dunne was paid close to half a million and was routinely put up at the Chateau Marmont or the Beverly Hills Hotel during the Menendez and O.J. Simpson trials even though he was becoming imperious and overbearing: “Do you know who I am? I’m Dominick-fucking-Dunne!” This from a writer whose copy was often a mess and required the full-time attention of a very senior editor. Equally unflattering was the malice between Nick and his brother, John Gregory Dunne, who wrote to Graydon calling the VF editor a second-rate, provincial, culturally unlettered ignoramus who knew nothing about good writing at a time when the VF masthead was arguably stacked with more gifted journalists than any magazine in history doing exceptional work.

Graydon’s forensic telling of Marie Brenner’s “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” from 1996, about whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand going public with evidence that the tobacco company Brown & Williamson had long suppressed proof that nicotine was addictive and that cigarettes contained added carcinogenic material, reads like textbook journalism about textbook journalism. Mindful of the kinds of mistakes that wind up in the first paragraph of your obituary, Graydon draws a comparison to the VF story naming Mark Felt as Deep Throat, illuminating the way a difficult, dangerous piece was put together. Those were the days.

By 2016, Si had been retired for a year; Time Inc. was in smithereens; and a combination of audience upheaval, ubiquitous social media reach, and lack of innovation was eroding Condé Nast as well. Anna Wintour, by then Condé Nast’s editorial director, called Graydon and “blithely” informed him that VF ’s photo, art, copy, and research departments (almost half the staff) would be moving from the magazine to a central unit reporting to her. This was scorched-earth cost cutting that would destroy VF as Graydon had edited it since 1992. He signed a nine-month contract that would take him through his 25th-anniversary issue and rented a house near Cap d’Antibes where he could enjoy longer naps and see if there was anything left in the tank.

As for Trump, the Donald had tried a new strategy when Graydon got to VF, praising an issue or whatever, sending Trump ties and Trump vodka and even an invitation to Trump’s 1993 wedding with the actor Marla Maples, which Graydon attended “out of journalistic curiosity,” but the transactional truce would never hold. In 2013, Graydon assigned a story on Trump University, the “fraudulent self-help racket,” and they were at it again. Trump wrote directly to Graydon: “I just heard you are trying to put yet another ‘hit’ on me through writer William Cohan. You’ve been trying since the terrible GQ cover story you wrote in May of 1984. After that, with your failed (which I predicted) SPY Magazine (I actually have very long fingers) and then Vanity Fair…”

Finally, only days before Trump descended the escalator announcing his candidacy for the White House, he sent Graydon a nearly 20-year-old tear sheet of a magazine ad for his ghostwritten memoir The Art of the Deal. He had circled his hands in the photo of himself with a gold Sharpie and written, “See, not so short!” Graydon sent it back with his own note: “Actually, quite short.” That was the last of it, nothing since then, but the long venal timeline of the short-fingered vulgarian still points with shame at the so-called balanced coverage that landed Trump in the White House in the first place.

Graydon spent much of Trump’s first term in the South of France and is planning to move back for this one. The next VF editor, the gifted Radhika Jones, would encounter the same poisonous office vibe that Graydon found when he followed Tina Brown, but radically diminished resources. Without the kind of support Graydon got from Si, she would have to fire many staff members, some of them earning highly inflated salaries by new industry standards, compliments of Graydon and Si.

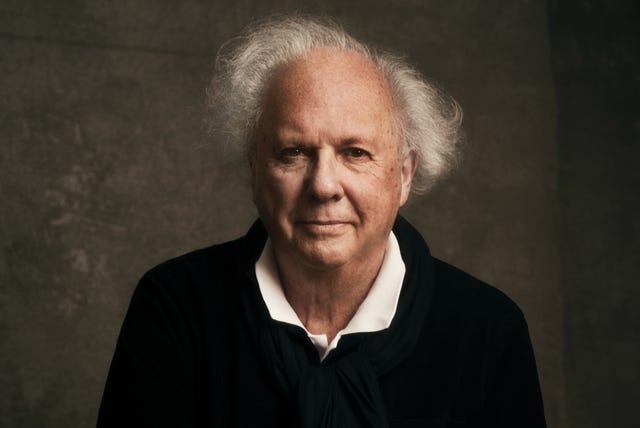

On the cover of Graydon’s new book is a handsome picture of him in perhaps his 40s. On the title page is a second byline, “with James Fox,” the James Fox known for White Mischief and the Keith Richards autobiography, Life. Graydon explains in acknowledgments that he needed narrative pacing from his old friend, or readers might have been stuck with a book that started with his birth in Toronto’s General Hospital and continued linearly from there—which it does not. What is important, though, is that as a boy in Ottawa, Graydon feared he was “destined to become little more than one of those faceless, nameless men in the scenery of someone else’s better life.” From then on, not unlike the title character in The Adventures of Augie March, the novel by another Canadian, Saul Bellow, young Graydon encounters numerous characters who attempt to shape his destiny, but he defines his own. In his blurb for my memoir, which I pointed to in the fourth paragraph of this essay, Graydon wrote that I had led “the beau ideal” of an editor’s life and written about it better than anyone anywhere. Graydon was wrong about that.•

Terry McDonell has published widely as a journalist, top-edited a number of magazines, and was elected to the American Society of Magazine Editors Hall of Fame in 2012. He is president emeritus of the Paris Review Foundation and most recently cofounded Literary Hub.