The American West has been the subject of speculation, scrutiny, and debate for centuries, and the maps that follow give us a glimpse of that history. In a pullout folio for Alta Journal’s Issue 29, author and historian Susan Schulten compiled numerous maps to demonstrate this, beginning with a map dating from 1540 by German scholar Sebastian Münster to a racially charged layout of San Francisco’s Chinatown in 1855 to 1949’s pilot’s topographical view of United Airlines routes. Schulten sits down with Alta Live to walk us through these eye-opening historical documents, demonstrate our evolving understanding of the American West, and answer all of our burning map questions. We’re turning off the GPS and turning on history in this very visual conversation you don’t want to miss!

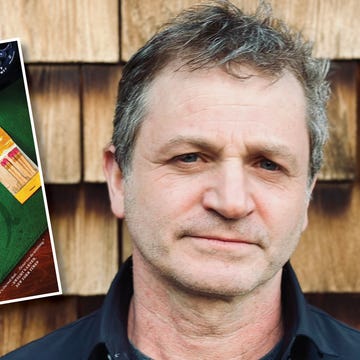

About the guest:

Susan Schulten is a Distinguished University Professor of History at the University of Denver, where she has taught since 1996. She is the author of several books that use old maps to tell new stories about American history, including A History of America in 100 Maps (2018), Mapping the Nation: history and cartography in nineteenth-century America (2012), The Geographical Imagination in America, 1880–1950 (2001), and—most recently—Emma Willard: Maps of History (2022). She is currently researching a book about the 20th-century mapmaker Richard Edes Harrison, and in 2025–2026, she will serve as the state historian of Colorado. Her work has been funded by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Mellon Foundation. At the University of Denver, Professor Schulten teaches courses on the Civil War and Reconstruction, America at the turn of the century, the history of American ideas and culture, the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, the Great Depression, the Cold War, war and the presidency, and the methods and philosophy of history.

Here are some notable quotes from today’s event:

- On early maps: “Part of what’s so great about these early maps—I mean, we’re dealing with a very dark period of history, but the fascinating and curious part for me is always to try to remember that maps are a combination of argument and best knowledge.”

- On maps and women’s suffrage: “Women started to draw maps and to show the West as this white mass which took up a third of the country. 'Look at how the momentum is shifting, look at how women are moving suffrage from West to East.' Geographically, in terms of space, they were leveraging all those winds in the West to say, ‘Look, the map proves that the future is one with equal suffrage, with women’s suffrage.’”

- On maps and how they explain our lives: “What you’re looking at here is the backside of a utility bill from 1922. We didn’t put the dimensions on there, but I’ll show your audience. It’s a little postcard: They send it to you, you pay your water bill, and on the other side, they explain your water rates. They explain that your water comes a long, long way through the L.A. Aqueduct—the greatest engineering marvel of that time—transporting water hundreds of miles from its source down to your tap. And that’s why it’s not free. To me, this is an example of an ordinary map, an ephemeral map, telling us how these things navigate our lives.”

- On Indigenous deerskin maps: “The ones that I find most fascinating are from the early 18th century, which are on deerskin. They represent relationships, as opposed to just space. The tribes are represented in terms of size, in terms of their power, whom they’re connected to, and whether it’s the colonies or other bands of their confederacy.… What’s really interesting to me is the way that many Indigenous tribes represented space in terms of time it took to traverse it.”

Check out these links to some of the topics brought up this week.

- View our pullout folio by Schulten in Issue 29.

- Buy Alta Journal’s map of California.

- Learn more about History Colorado and its State Historian’s Council.

- Check out the Catawba Deerskin Map, available through the Library of Congress.

- Look into Schulten’s A History of America in 100 Maps.•