Now write this: A quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog,” I say to my 12-year-old daughter, Tess. She puts pencil to paper and starts a shaky sequence of cursive loops and lines, tasked with writing a sentence that contains every letter of the alphabet. Tess suddenly pauses. I repeat the sentence. She taps her eraser.

“But what if the dog is actually depressed, and everyone just thinks she’s lazy?” she asks.

No doubt, parents who homeschool their kids are accustomed to existential questions during lessons. I’m not one of them. I only recently took on the role of amateur educator when I found out Tess couldn’t read script. (One day, she squinted at a handwritten note from her grandmother and shook her head.) I was floored. That revelation led to another: Tess, a sixth grader who consistently got As at her terrific charter school in Los Angeles, didn’t know how to sign her name or write in cursive. My husband and I both write movies and TV shows for a living. We still compose what we call “like letters” to each other. We took her ignorance personally.

This article appears in Issue 25 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

But my daughter isn’t the only kid who can’t forge a check these days. Here’s why: In 2010, a consortium of governors and state school officers plucked cursive from the Common Core education standards for kindergarten through 12th grade. Schools in the United States could omit the script-handwriting lesson plan. The reasoning? Kids needed keyboard skills more than penmanship prowess. Plus, the time spent on crossing t’s and dotting i’s could be better devoted to math and science instruction. The initiative was hardly Orwellian. Some states, like Texas, require cursive to be taught in all public elementary schools; in others, like California, the school districts call the shots.

By 2013, districts in seven states, including California, had reinstated cursive as part of the curriculum. Three years later, at least 14 states had joined Team Quill, according to CNN. (L.A. became a pro-cursive district in 2019.) According to the National Education Association, 21 states—most of them in the South—now require cursive to be included in public school teaching plans. This is a polarizing issue among educators, politicians, and even pupils. Headlines in the New York Times range from “What’s the Point of Teaching Cursive?” to “A Defense of Cursive, from a 10-Year-Old National Champion.” In other words, it’s on.

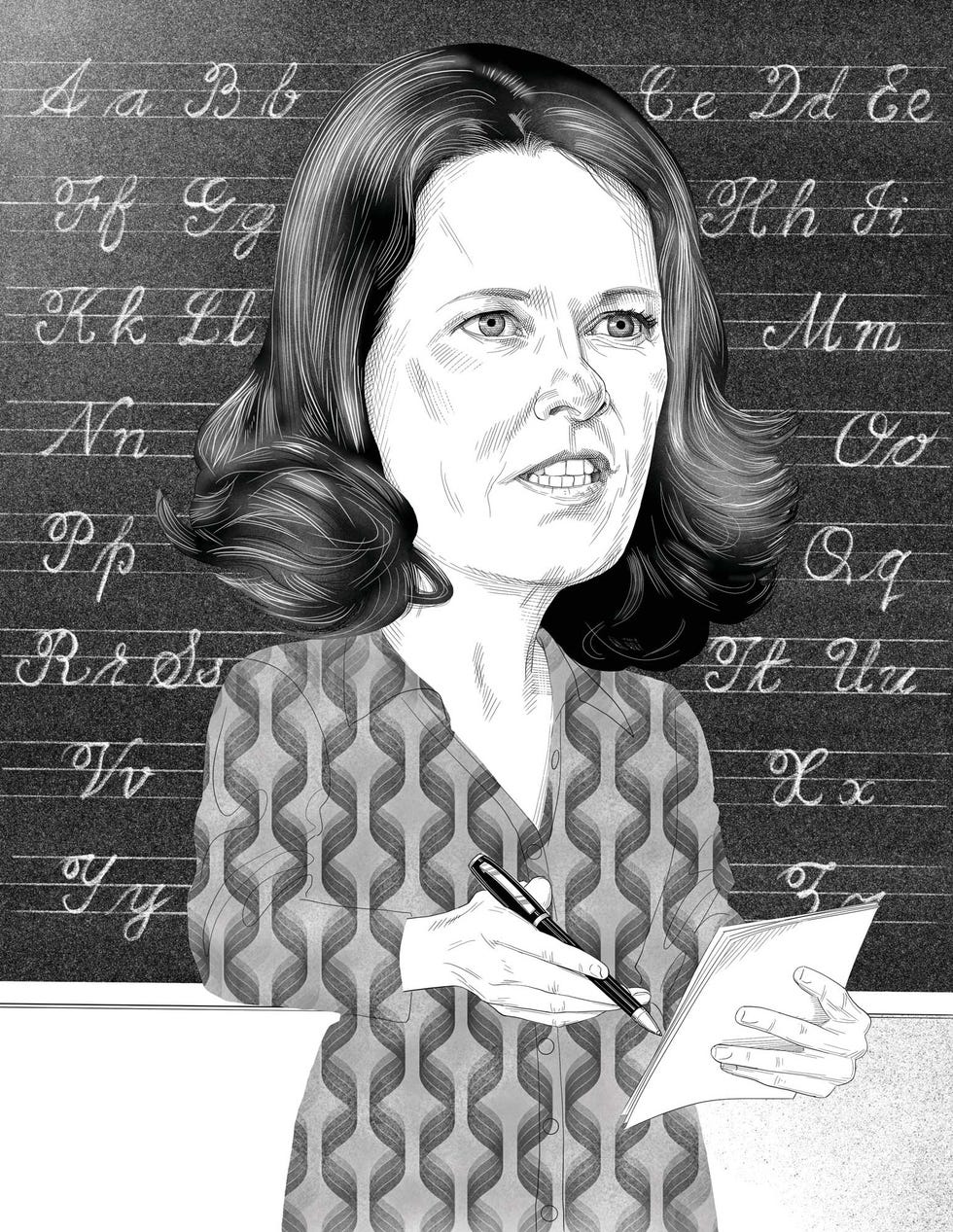

If COVID had not detonated the scholastic agenda at Tess’s school in 2020, she would have learned longhand in fourth grade. That year, remote learning called for more improvisation than a John Coltrane concert. Teachers had to engage over Zoom, and cursive got lost in the pandemic shuffle. But “even in a post-COVID world, the importance of cursive remains vital,” says California assemblywoman and veteran schoolteacher Sharon Quirk-Silva, who’s sponsoring legislation to make cursive a statewide subject like reading or spelling. Her bill is awaiting a vote from the state senate before it can go to Governor Gavin Newsom’s desk. “The unique cognitive and developmental benefits associated with cursive writing make it a valuable skill for students, irrespective of the challenges posed by the pandemic,” Quirk-Silva says.

My daughter didn’t agree with the assemblywoman. Before I could enroll Tess in homeschool at our dining room table, I had to make her fall in love with cursive. How else could I convince a social but cynical girl to give up 10 minutes a day of summer vacation to learn how to write like a founding father? First off, I gave her a phone. (Relax. She was already due to inherit one of our old iPhones for the start of seventh grade.) But to try to get her to swoon over script, I also made her watch a Dodgers game on TV with me. When pitcher Clayton Kershaw took the mound, I excitedly pointed out the iconic script emblazoned across his jersey. “Look at how the s circles back to rocket through the lower loop of the g and underlines the name of the team,” I said of the bright blue logo designed by Lon Keller in the 1930s. “That’s the beauty of cursive. For the letters, it’s teamwork!” Tess rolled her eyes and shrugged. Not impressed.

When I was in elementary school in the late 1970s, nobody bribed me with a rotary phone to learn anything. In third grade, we all had to study cursive, first by scribbling a sea of waves—or a series of the letter u. These were the “strokes” that introduced our wrists to waltzing across a lined page instead of plodding along as when we printed. At my school, we traced fat, fecund vowels and then moved on to trickier, rickety consonants like f and k. “Just think of the letters kissing each other,” my teacher told us as we wrestled with our yellow pencils, pink tongues between our teeth. Not only did I master a standout signature that soared and swooped like a paper airplane, but I also learned how to sign my mom’s name on my lousy report cards peppered with those rickety Fs.

A handwritten note says more than laugh lines do about your generation. If you’re a baby boomer, you likely learned to write cursive using the Zaner-Bloser method, which replaced the Palmer method in the 1950s and was all the rage in U.S. classrooms until the late ’70s. Perhaps you recall holding the page at a slant and focusing on the flick of your wrist rather than on your fingers? If so, you also added a lower loop to the letter p, and your capital Q had a lazy cat tail. Many Gen Xers who, like me, studied handwriting while Jimmy Carter was president practiced the more streamlined D’Nealian method, developed by Michigan schoolteacher Donald N. Thurber. Our letter p’s have sticks instead of loops; capital Qs look like the number 2. Today, most kids who learn cursive in the classroom study a modern variation with elements of these two styles.

My next gambit with Tess was more successful. We took a field trip to World of Barbie, a 20,000-square-foot, Pepto-Bismol-hued homage in Santa Monica. “Cursive alert!” I shouted at the entrance, tracing the famous logo’s vivacious B and closely spaced, lilting script letters. Tess glowered at me, but I persisted. “Look at how every letter bounces at a different height like they’re all dancing,” I said. Tess smiled and observed, “The i is chewing gum and blowing a bubble.” We high-fived. I went on to tell her that the company Mattel experimented with redesigned block-letter versions of the original 1959 cursive Barbie logo over five decades—and ultimately, it went back to the first scripted iteration in 2009. Tess was now slightly smitten.

Clearly, getting TikTok-obsessed kids excited about old-fashioned handwriting is no easy feat. Lauren Mooney Bear, president of the American Handwriting Analysis Foundation and head of its Campaign for Cursive initiative, can relate. “We just added a creativity category to our annual Cursive Is Cool handwriting contest so it’s not so stinking boring for the kids,” she tells me, noting that prompts like “Tell us about a day in the life of a pencil” or “What if you were the pen of your favorite celebrity?” encourage children to tell stories about the art of writing. “One kid this year wrote, ‘I hate handwriting, but my teacher says I have to do this.’ He didn’t win the contest, but I thought he should get props for being honest,” Bear says with a laugh.

Beyond its practical application and primal form of expression, handwriting also stimulates the brain. Research has long shown that we learn more and retain more information when we write rather than keyboard. (I scribble my to-do lists on a pad instead of typing them into my iPhone for that very reason—and I delight in aggressively crossing off each completed task.) But a recent study published in Frontiers in Psychology broke new ground by, for the first time, monitoring the brains of 12-year-olds as they wrote. “Typing on a keyboard only requires simple finger movements that are identical for every letter you type. That is probably why children who have learned to write and read on a screen have difficulty with letter recognition,” says Audrey van der Meer, an author of the paper and a professor of neuropsychology at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. “Writing by hand as opposed to typing also seems to put the brain in a more creative state.”

As a writer, I am much more inventive on the page than on the screen. I’m also more patient with my thoughts, letting them slowly bleed out of me rather than violently hemorrhage. More importantly, I can’t flit away to check email or troll eBay for vintage Mexican pottery. Ernest Hemingway, who joked that he could wear down seven pencils in a day, once said, “I write description in longhand because that’s hardest for me and you’re closer to the paper when you work by hand.” Susan Sontag wrote in felt pen or pencil on legal pads, which she referred to as “that fetish of American writers.” Quentin Tarantino, J.K. Rowling, and Neil Gaiman all scribble down first drafts.

When I reach out via text to the prolific Pulitzer Prize winner Louise Erdrich about her penchant for writing novels on scraps of paper, she immediately responds, “I don’t like how easy it is to edit on a computer. I mean, you can save your edits but I wouldn’t go back to them. It’s like the computer has digested them and they belong to the lower gut.” She pauses for a moment and adds, “My script is thin, swift and slanted to the right with no dots or crosses. Lately, my lowercase letters are triangular. I can recognize eras in my signatures.”

After a week or so of cursive homeschooling, what I can see in Tess’s signature is her personality. Her T is bold and flamboyant, which reminds me of how she likes to make a boisterous entrance. But the lowercase letters of her first name proceed more cautiously like spies to the corners of the room. Tess is her own voyeur and prefers to see how people react to her from all angles. Now she’s preoccupied with testing out her signature on Post-its, napkins, her bedroom wall.

My own autograph finally looks legible again, too. For the past decade or so, I have barely scratched out my name on checks and contracts. (My semi-romantic letters to my husband have devolved into a messy scrawl.) In practicing strokes and showing Tess how to write in longhand, I’ve fallen back in love with the beauty of letters, a family of words, the finality of punctuation. My wrist aches after our 10-minute lessons, much as my biceps protest after I lift weights. I’m even writing in a journal in the morning to rev up my imagination.

Ultimately, though, we never get through the entire alphabet. R is where we call a truce. Tess is the quick brown fox who wants to hang out with her friends, and I am the lazy dog who lets her leave the house before we finish her cursive lessons.•

Monica Corcoran Harel is a screenwriter with a media platform for women over 40 called Pretty Ripe and loves being middle-aged.