My family moved west in 1984, piling into our mud-brown Mazda station wagon with clothes and snacks for a month, our new dog curled into a ball in the back. Tail thumping any time we said her name. Tracy? Thump. Tracy Tracy Tracy, thump thump thump. Like the sound of freeway joints we passed over as the nation unfurled on the highway out of Pennsylvania, into Ohio and Indiana, the moving van with all our earthly belongings rolling ahead of us.

We arrived in Sacramento that fall, it was the middle of Reagan-era America, and my new, sunblasted school had an entirely different way of measuring students’ progress. The first big test I remember taking at Schweitzer Elementary was not a math or science quiz, but the presidential fitness exam. All 30 of us in my grade were marched out of class like little cadets of future buffness and run through the paces doing push-ups, sit-ups, the monkey bars. We were dangled from a high beam and told not to be quitters. Do one more pull-up. Feel the burn.

They saved the hardest bit for last. A timed run. Only it wasn’t over a fixed distance. A teacher had lined up two cones 200 meters apart, and he began blowing a horn every 30 seconds. If you couldn’t run from one cone to the other in that time period, you were out. Blat went the horn, and we were off. Kids don’t run well or smartly. They sprint everywhere or lag. Some forget what to do and just stand there. By the fifth horn blast, only a few of us remained, and by the seventh or eighth, it was just me and Jenny Johnson, albino pale, nearly six feet tall, a daddy longlegs at speed.

I could hear her huffing behind me in between heckles.

Run, you little shit.

And then there was silence. Not a churchly silence, but a drop in sound so total, it was as if the universe had been muted. Through the tiny apertures of my eyes, I could see the field, its dry tan grass. I could feel the heat pulsing off it in waves. All the while, the sentient part of me, the one that always watches, was protected behind this machinery of breath and blood—my body. The horn continued to blast and my legs continued to glide and pump. Meanwhile, the landscape around me tilted sharply into view. The gouged wooden fence around the soccer field, a horse on the other side blinking, curious. The rust-colored sadness of the jungle gym bars, my low school behind. The sky above like a huge blue lake. I experienced with the force of revelation that all of my body—from my heart to the bones of my skull—was simply a carrier for the primary mechanism, this roaming, zooming lens of silent regard. This mechanism was the miraculous instrument that, if I treated it right, would orient me through the world.

This article appears in Issue 25 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

And it has—that was 38 years ago, and I have been running ever since. For one decade, I competed. Laced on spikes, splay-legged, on the infields of tracks, before dashing through one 1,500-meter race after another. Come fall and winter, I was always shoving on flats to splash through muddy fields and up grassy hills cross-country. It was a thankless sport, weather-wise. Growing up in the San Joaquin Valley, I ran in temperatures of 100 degrees, and later, in college, back East, I ran in the snow. I once raced an 8K across the Gettysburg battlefield among the ghosts of the Union dead soldiers. I ran indoors. I ran on rooftop tracks. I ran up 30 percent inclines beneath the redwoods. I ran with future Olympians and I ran with thousands. Sometimes there were crowds; more often, just small windblown clutches of family members. Under gray-cobalt skies; around klieg-lit college stadiums; in the dry sunbaked ovals of dirt tracks scattered around Sacramento. Through it all, the silent puffing of strangers and friends. Then, as always, the silence: just me and the periscope—that lens that was me—moving.

I knew that once I had graduated from university, I would be done competing. I’d reached the end of my talent—or my desire to reach it, which, in the end, is the same thing. For a brief time, it seemed possible I could come close to a four-minute mile. But to race seriously requires a dedication to pain that is almost religious. And time. Running 90 miles a week—as I did back then—requires logging a minimum of 20 hours on the roads between Monday and Saturday. I used to look back on this immensity of time—100 hours a month, 1,200 hours a year, 12,000 or more hours over a decade. A year and a half of doing nothing but running. I could have learned Mandarin. I could have read War and Peace, finally—learned Russian, read it again, and still had time to learn to cook every meal served in the book for my mother, the Russophile. Her shelves were full of Solzhenitsyn, Turgenev, Tolstoy, and Dostoyevsky. Light reading. Instead, I ran.

I wasn’t just moving through the world, though. It was about more than the dull polish of discipline, too. The more I ran, the more I sought the opening up of that inner scope. The one that was looking. Absorbing. Then I began doing it naturally without thought or design. Dreamingly. It wasn’t a high. It was a submersion deep down into myself that made it possible to forget myself. To leave it behind. And to see. To run like this shaped a sense of place and space so deep and transcendental that even once I stopped moving—it did not. As in, all those hours on the roads turned my mind into a mapmaker. I can’t get lost and I almost never forget a place today.

For example, I could guide you through my suburban Sacramento neighborhood now, house by house: out the door, down Ladera Way to our palm tree, a right on Stollwood, a left on Winding Way, with its column of trees genuflecting onto the road, past the sci-fi bookstore, the yellow fire station with the guys who never had the checkbook to pay for the newspaper I delivered to them every morning, an 11-year-old pedaling his bicycle in the dark at 5:30 a.m. Then onward to Manzanita, one of the large four-lane roads, always clogged with traffic, and where for a brief part of one summer I worked at a small stand scooping ice cream.

I remember all this not simply because I lived there, but because one of the training routes for my track team followed this path on an eight-mile run we called Manzanita.

Manzanita. Fair Oaks, Winding Way…these names…they were not just the names of streets, but the names of our routes, too. And I could walk through them backward still, if I had to today. I remember where the speed bumps were, where the trees obscured a driver’s view of the road, at the place where Manzanita curves before turning into Fair Oaks, where 32 years ago this summer a man about my age leaned out his car window and said, You kids are going to regret all this running on concrete when you get to be about my age.

To describe running thus could make it sound like a way to become a well-stocked Google Map. That it is my Proustian madeleine. This isn’t what I mean.

So what do I mean?

I mean that running made me porous to surroundings in ways I don’t believe I would be had I spent all that time in cars. To travel through space in a car, after all, is to be unmoved by it through almost every one of your senses but sight. Sure, if you rolled down the window, you might smell the whiff of mulch blowing off a field drowned by rain. But would you appreciate the length and breadth of such a field if you passed by it in a car? Would you feel in your feet the pebbly edges of it, where the grass ended and the raised part of a roadway began? Would your inner equilibrium register how roadways have to be raised, so that rain can flow off them in periods of heavy downpour? And would your nose have the time—this is crucial, movement and time being so intimately connected—would it have the time to sense the layers behind a mulching field? The cold, furry pulse of stagnant water; the chocolaty scent of earth; the layers of history built into how a place smells? It is how the natural world tells its story.

I should say here I am not describing an imaginary field. What I’m talking about is an area next to a park where my cross-country team ran mile repeats for practice between September and November in the late 1980s and early 1990s. When the rains came every fall, after our long, dry, blazingly hot Sacramento summers, the parched fields would flood, and so between the first 400 meters and the halfway mark of each repeat, in that glorious period of any race when there is no pain, just a settling in to pace, into an order within the pack, when your eyes latch on to the shoulder of the runner in front of you, your legs far beneath the mind like a kind of ambulatory fan, blowing you forward, effortlessly, your feet making adjustments for differentials in terrain without your mind thinking about them, because you’re in that fugue state within the mile, at that moment we’d always pass the drowned fields. For a brief stretch, I’d float out of my body and listen to the field. Feel the air coming off it. See the changes since the previous week. A new browning to one of its corners. The scatter of leaves on another. Then I’d drop suddenly and abruptly back into my body as we hit the halfway mark, the assistant coach yelling out our half-mile splits: 2:20, 2:21, 2:22, and that’s when the pain would begin.

When I moved to New York City in the mid-1990s, the last thing I wanted to do was run. I was done with the pain. The constant aches. The flirtation with masochism. The cowlike relationship to food you develop in order to consume enough calories not to wither away. I probably would not have run again had I not moved to the city with two of my cross-country teammates—Scott and Brenn, neither of whom, at first, wanted to run either. We arrived in Manhattan together in the summer of 1996 like escapees from a cult. Our mornings yawned deliciously at us. No more sour-stomached early jogs. No more attacks of the dreads over an afternoon race. We could eat what we wanted, sleep when we wanted; our weekends were ours again. All of us, understandably, and idiotically, started smoking cigarettes.

By the fall of that year, we’d found a sixth-floor walk-up in the East Village recently vacated by three goth chicks who’d painted the ceilings blue and had left their black light behind. The apartment was far cooler than we were—so we honored it by throwing parties, pumping techno out the windows and placing punch bowls around it full of ironically named drinks. The F Train. The Cure. After the guests left, we’d clack up the stairs in our Saturday-night shoes and smoke Nat Sherman cigarettes on the gooey tar rooftop. We gazed out at the industrial seethe of Lower Manhattan and felt ourselves transformed.

But we weren’t—we were just naïve, uncosmopolitan suburban athletes who’d merely seen some of the gestures of adulthood and adopted them, claiming the carvings of time before actually feeling its knife. So we played at urbanity when it actually frightened us. Could we really stick it out in the city for a year, for two? Ten was inconceivable. Within months, we had reverted to type. We were bookish nerds who liked the world at a remove. We began reading again, squirreling ourselves away at café tables for hours at a time; it was an easier way to experience experience. The books we read then tackled us hard, though. They were not for study; they did not possess concepts to master our articulation of; they felt like stories someone wrote because they had to. Giovanni’s Room, by James Baldwin; Night, by Elie Wiesel; Plainwater, by Anne Carson. They were books about the entwinement of love and loss and time—and we were no longer sequestered in classrooms with a dozen other people our own age. It felt like discovering a kind of book that was made of actual flesh and bone and we’d been playing with dolls.

As fall tipped into winter that year, we found ourselves reverting to type in another way: we woke up one morning, laced up our shoes, put on our shorts, and went for a run. After spending so many hours on relatively safe roads and protected trails and well-tended tracks, to be jogging up Crosby Street in SoHo over cobblestones, dodging cabs and rats and eventually garbage trucks, felt absurd. There’s a beautiful photograph by Thomas Richter of Crosby Street in the late 1970s. It captures so much—the pavement’s wide, crooked grin; the handsome, sober lines of the buildings’ cheekbones; the receding hairline of sky.

Down on the cobblestones, however, in 1996, Crosby Street showed a very different face. Everywhere we ran, one of those prehistoric garbage trucks lunged into view, as if we were being chased. We’d turn onto Prince and hang a right on Mercer, head toward Houston Street. Here comes another one. Trash collection was controlled by the mafia, or so we read, and the trucks often had the names of their drivers stenciled on the side—Marco, Claudio, Lino, Dino.

Finally, we outran the downtown brigade of sanitation trucks and we were into the flow of running. The morning silence of the city spread out around us, broken by its ridges and sighs, the sounds of bodies turning over in the final hours of sleep. A woman coughing at her sink while filling a teakettle. The cast-iron facades of SoHo were replaced by the humble redbrick townhouses of the Village. Brittle, bare tree branches scratched at the sky.

I saw a whole new city that morning, moving through it on foot as a runner. Gulping down air and searching for soft surfaces. It was a New York built atop and around and through a natural place that sustained it, even as the city itself pretended—save for a park or two—that this natural foundation wasn’t there. How strange to respect this sentient, living space as a Californian, so used to encountering this living earth head-on; to feel a patience radiating from it with the acres of concrete poured across its body; to see the other living things that made their homes there, not just the humans. Running in cities speeds up all the reaction times you must cultivate to move safely through them, after all. Looking left and right when crossing a boulevard, listening for traffic, watching out for someone lurking between parked cars. With this heightened awareness comes a feeling of that place as an active agent—not a scene, not a stage set, not “New York” or “Paris” or “Rome” or “Karachi,” but a place alive around you as you move through it.

I did not expect to have such an urban life. I thought I’d leave New York after a year or two. I did, in fact, but within a year I was back, and save for five years in London, I have lived there ever since. I wasn’t a traveler when I began my life in cities. For my family, a vacation meant going someplace we could reach on two tanks of gas. Monterey, say; San Diego if we pushed it. I didn’t leave the United States until I was 25. By which point, I was a book critic, perhaps the most sedentary job ever created. But accidents of the heart—I fell in love with someone from Lebanon with family in London—and an unexpected turn in my professional life, when I was hired to edit Granta, the U.K. literary magazine, made me into the kind of traveler my stern, fun-eschewing father (who loved that I ran something as un-fun as cross-country) used to scorn. Scooting off for long weekends in Porto or Rome. Sitting in the sky for 15 hours so I could attend the launch of the magazine in São Paulo.

Becoming a person so uncoupled from where I was from—Sacramento, after all—caused me to live in ways I now see as rather stupid. In my late 20s to mid-30s, when it was clear I’d spend my life in cities, I began to mimic the worst sides of them. The concentration of people and businesses in urban areas can make a city feel like a factory for industry and creation. A kind of machine that never sleeps. Something suprahuman.

As a watcher, I found myself trying to deduce what the city wanted me to be. Because the city I lived in never slept, neither did I. Because the city I called home heaved with things to do, I went out and did them. At the time, it occurred to me that this was a continuation of my childhood pursuit of the elusive it—only in a new setting. What was it that I wanted? Where could it be found? What corner of the city contained it? Or who?

My body in this urban lexicon became a kind of transportation device I needed to feed, and occasionally service—a dependable, supremely complex, yet slow-moving car. But that’s about it. The periscope in me I had long since packed away. There is nothing more machinist than a gym, and yes, I joined them. Instead of running through the city, I joined a glass tower of fitness where I could run above it. Looking down at the walkers and wanderers with a small balloon of contempt in my heart.

The wondrous thing about a body, though—one of its many wondrous things—is that it has a will. A mysterious unspeaking sentience that is animal in nature and communicates in the same unknowable but tangible language as that drowned field or the natural part of New York City telling its stories. The body is part of this living ecosystem; it has needs that, if denied long enough, force it to subvert the waking mind that controls it.

I don’t remember when it started, but eventually I found I couldn’t keep up. Glitches in the machine were developing. The city-life night, once so full of mystery, seemed to grow fangs. I watched as bodies around me began to break down. I saw my mother die. There was comfort in this: she had been sick a long time. And I had prepared for it by lifting weights—the metaphor so obvious that had my life been a book, I would have criticized it as being a bit on the nose. Then she was no longer. For a time I was crazed with grief. How to bury the sky. The city a columbarium of ghosts.

Then my body revolted. It had had enough. It needed to move at a slower pace, and so—contradictorily—it wanted to move.

And so it was that, a decade into a life of traveling, I rediscovered the pleasure of running. I wish I had a story of the exact day this happened. I don’t. All I remember is that several years into my job in London, after taking up boxing, and wanting to be warmed up before my trainer came by and began punching me in the face, I started going for runs—before we sparred. My instructor’s full-time job was training horses for dressage. She was not particularly happy to find I had been working out before we worked out. Am I not giving you enough to do? she asked one morning, throwing a jab at my chin. No, no, I remember replying, while ducking. It just wakes me up.

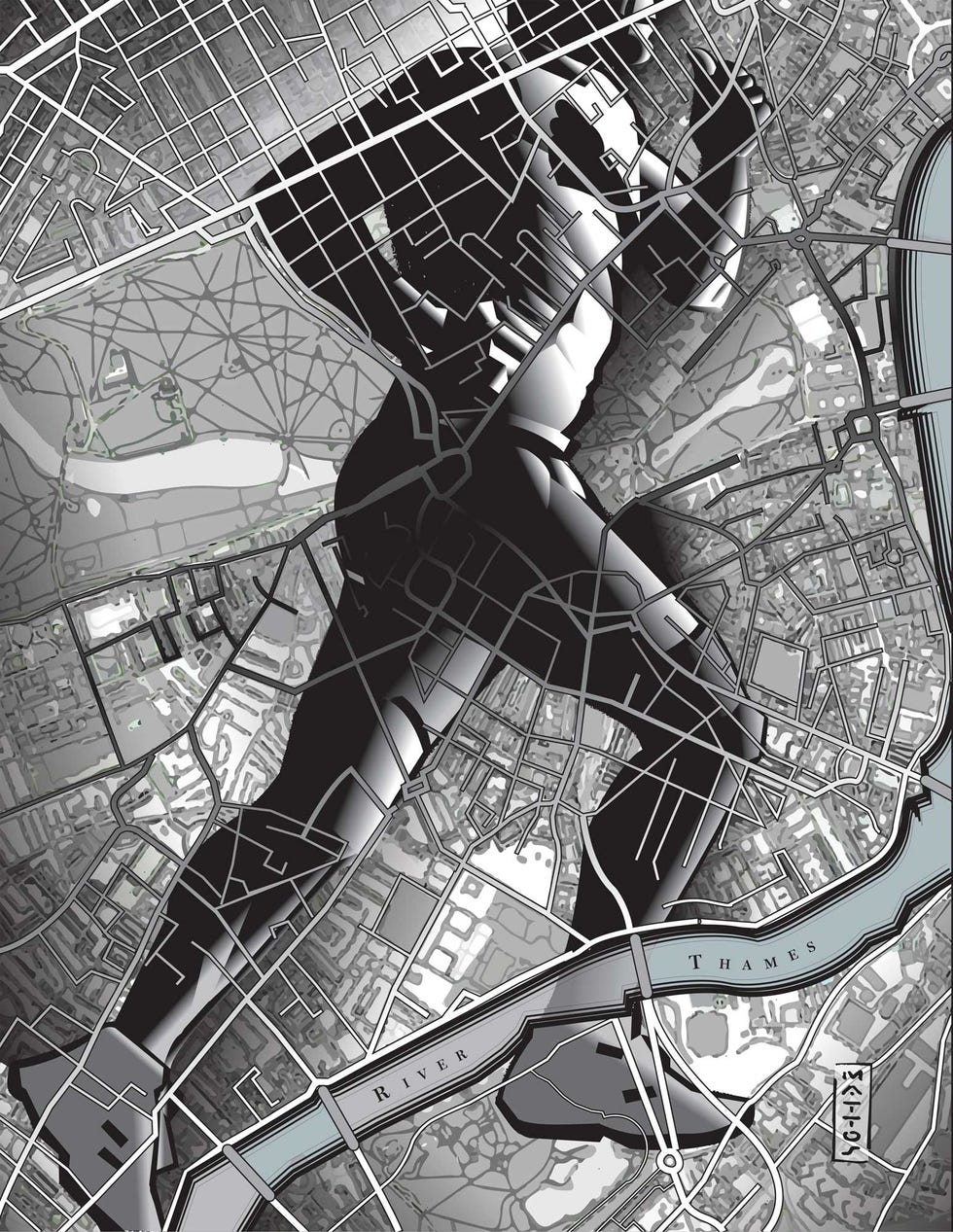

It was more than that, of course. For years, I’d come to London to stay with my partner and her family. We’d head into the city for dinners with friends. I’d nip out for the occasional jog around Wimbledon Common. When I moved there alone to work, though, I realized I didn’t know the city. I’d followed my partner in and out of it on the District Line, not paying much attention. And after I got an apartment there, years went by before I realized you could narrow my movements down to a few key paths to and from work and the events Granta hosted.

It was pathetic, frankly.

Hitting the roads again, though, I began to appreciate the city anew. The way so many streets were canopied by trees. It was a great place to breathe compared with New York. All those white limestone houses in West London, where I lived, appeared similar at first, a bit pretentious, if I’m honest, but as I passed and repassed certain streets, tiny differences emerged. The placement of a conservatory or flower box. The different shades of orange lurking within the seemingly same red doors.

I became a lover of parks. Hyde Park was at its best very early, when the ducks were still waking up and less insistent on being fed, when its long pebbled paths could stretch out in all directions with their dignity. Holland Park was finer later in the morning, once the people on their way to work had cleared Aubrey Walk, which linked Kensington Gardens to Holland Park Avenue. Kew Gardens was not a place to run at all but somewhere to walk yourself into a trance, when the urge to name what was around you fell away.

Running, you never feel compelled to see the normal sights. To name and claim as we do in cities: taking pictures, tagging monuments. I don’t think a single guidebook will ever say, Here’s a thing to do—run by Parliament and you can enjoy the sight of members of the House of Lords going to work. There are no points for running through the Tate Modern; you don’t see the work faster—you just usually get kicked out. But on the roads, on sidewalks, on trails and paths, running through parks, you see the city going about its business being a city. Landmarks be forgotten.

By the time I left London in 2013, I had become a runner again. I had all the shitty shorts and many T-shirts, the rotation of sneakers and the minor ailments, but also a mental map of all the places I liked to go in a variety of cities I often passed through. This was more than an athletic version of favorite restaurants. It was an ongoing relationship to a physical place. Each time I visited Seattle, climbing its hills, crossing its many bridges, I appreciated how recently the city had crawled itself away from the forests around it. In Tokyo, the city’s destruction in World War II was as fresh as its brand-new roads, their silken tarmacs. It was impossible to run across Beirut without feeling a charge in the air as I crossed neighborhoods. Sarajevo’s Miljacka River was a slow-moving reminder of what terrible things it had carried.

The past is never the past in so many cities, but if you wake early—as seems to me the best way to run—the natural cycle of a day tempers this ongoingness. You don’t have to be in Florence to see how morning light ennobles stone. Birds are often about, searching for food. And not just the usual ones. I’ve seen peregrine falcons in the Jardin du Luxembourg and great cormorants fishing along the Bosporus in Istanbul. Herons in Vacaresti, the enormous wetlands that were meant to be a human-made lake on the outskirts of Bucharest, one of Europe’s densest cities. It’s not that nature is just now reclaiming parts of many cities: it’s always been there.

As I’ve run through cities in recent years, a second layer of feeling has emerged in what I realize is a lifelong search for the elusive it, a sense that drew me up trees or out toward a ravine near my childhood house when I was small. That running is a way of becoming an animal again, of reminding myself of this animal nature. That the periscope isn’t a lens at all, but a removal of the layers that need to describe it as such.

Live in New York City long enough and you will find yourself navigating by what is no longer there. Most mornings now, I run down the West Side along the Hudson, past the piers that once had rotted boards, toward the ghost of the old World Trade Center, out onto the newly refilled landfill. There are birds on the river most mornings, sometimes even eagles, and this makes me a little more capable of facing a new day in New York. It often occurs to me that I’m jogging atop what used to be water. Then I circle back through Wall Street and into TriBeCa, past what was once a Bulgarian nightclub called Mehanata, where, in our 20s, my roommates, Brenn and Scott, and I went to dance, but never before 1 a.m.

Around this point in my run, I start promising myself I can stop and get coffee if I find a shop that was open in 1999. My choices are pretty limited, so it’s a good way to force myself to run a little longer. Near NYU, there are a few Italian cafés that date back decades—but they’re not the type of places you sit down sweaty. So I often cut east or west around the Village. Just recently, I headed home up Seventh Avenue and stumbled onto a portal to the past, Patisserie Claude. A tiny three-table, bare-bones French bakery run for a long time by, yes, Claude, who made croissants and cakes out of a kitchen the size of a Renault 5. In 2008, it closed and reopened with Pablo, Claude’s onetime protégé, at the helm.

It may as well have been my first year in the city. The croissant was still slightly denser and more textured than air. Flaky as ever. The coffee black as death, sweet as life. Standing under the awning in the rain, my sweaty running gear sticking to me, I realized I’d last been there exactly 20 years earlier—on a rainy morning just like this one. I’d taken the bus down to New York from Boston to start a new job, editing a guide to children’s books, and discovered upon my arrival that Brenn—from whom I was taking over the position—was moving. I’d then spent most of my day and a lot of my night carrying his furniture up six flights of stairs into his new shoebox of an apartment on Elizabeth Street.

At night’s end, I met a friend for a drink. She’d just given notice at her job and was moving back home to Chicago or some place. I wound up crashing on her sofa and woke up early to rain dripping through the trees behind her apartment on Bleecker Street. I ducked out to get us breakfast before leaving for work and found Claude around the corner on West Fourth Street. Its fog of hot-milk and warmed-sugar smells reminded me dearly of Caffe Trieste in San Francisco. As in that hallowed spot, everyone inside Claude appeared to be a regular. I was young and broke, and so buying breakfast felt like playing at adult living. To spend my last $10 on something the woman whose apartment I had stayed in might not eat, it was a stab at saying I’d had a crush.

It surprised me it’d taken me 20 years to step into Claude again, given how much time I spend at cafés. Then I remembered, whenever I walk through this part of the Village now, I skip West Fourth. It forces me to pass a bar a good friend once told me he went to in the 1950s and drank with James Baldwin. Hearing that story always thrilled me, but also left me with a wash of melancholy. My friend was the best oral storyteller I’d ever met, but he spent his life selling real estate on the New England seacoast. Talking about one day writing a book. James Baldwin was the best moral writer America had in its postwar period, and though it’s hard to conceive of it, he might still be with us had he spent a little less time drinking with strangers at bars.

I have these thoughts, and then I think, there is no adjustable grid for what can be expected—just a way to respond to what we’re given. It’s a hard way to be in a city that changes as much as New York. There are days when I run through Lower Manhattan in a state of bewilderment, like in one of those dreams where everything is the same, but slightly different. The bookstore where I bought a chewed hardback of Giovanni’s Room, closed. The shop on Ninth Street and Sixth Avenue where I heard Rebecca Solnit read from Hope in the Dark. Closed. The rare-book store operated by a guy who always wore a fisherman’s hat—closed, twice. It moved to Hudson Street briefly and closed again.

I don’t want to digress into a screed on how everything is over. But what I want to end with is this question: Where are we supposed to put memories that live on the same streets that created them, when those streets are both there and not there anymore? A small part of why I go to cafés now is that I still remember how precious were the dollars it took to buy a coffee when I was broke. To this day, I marvel that I can take a break and go purchase my own coffee. One of my most distinct memories of my first year in New York City, when I had hung up my spikes and was working as an editorial assistant: digging in my pocket for enough change to buy a coffee and having the barista explain to me that the woman behind me had paid for it.

And I guess I run in cities not just to see what’s there, to feel the pleasure of my body in motion, to wake up the animal in me, but also to remember the freedom of that initial liberty—given by my parents, how lucky I was—to search. To acknowledge that it is far easier in this world to remember what we have lost by being born into it. Most days, I try to do that by putting on my running shoes, and doing it one step at a time.•

John Freeman is the host of the California Book Club and the author of California Rewritten, among other books. He is the editor of The Penguin Book of the Modern American Short Story and an executive editor at Knopf. He lives in New York.